Situations vacant: The pandemic and employment trends in the Wolverhampton economy

By Professor Paul Sissons, Head of the Management Research Centre, University of Wolverhampton Business School

It is almost two years since the first national lockdown in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The functioning of parts of the national economy immediately altered. Sectors such as hospitality and parts of retail were closed, and significant numbers of office-based workers moved to working from home. The following two years have been punctuated by various levels of restrictions affecting different parts of the economy, while patterns of consumption have also shifted (for an example see Amazon’s recent profits). These changes have important implications for the labour market – the types of jobs people do, how much they are paid, and where their work is based.

Using a new dataset of job vacancy data collated by Adzuna we are able to examine the aspects of this changing labour market. The data contains detailed information about vacancies advertised online – covering the full range from large retailers, who recruit on a more or less constant basis, through to less common, specialist and niche opportunities. Online vacancies cover the majority of vacancies in the economy.

Covid-19 and job vacancies in Wolverhampton

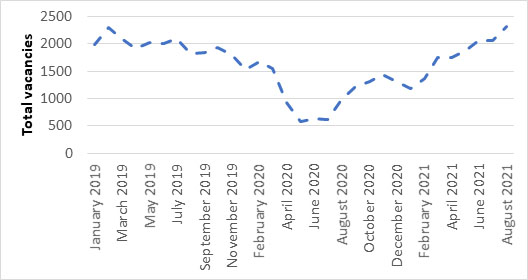

What can job vacancy data tell us about Wolverhampton during the pandemic? Figure 1 provides total advertised vacancies (using a monthly average) in Wolverhampton local authority area and how these changed during the pandemic. Total vacancies were gradually declining (pre-pandemic) during the second half of 2019. There was then a very rapid decline in the number of vacancies advertised from March 2020, as the country entered a national lockdown. During May to July vacancy levels were less than a third of those seen in early 2019. Vacancy levels then rose following the partial lifting of restrictions, before falling again (although by much less) in response the second and third lockdowns. Since March 2021, vacancies have recovered strongly to reach levels comparative to those seen pre-pandemic.

Figure 1: Total advertised vacancies: Wolverhampton, 2019-2021

Source: Author Analysis of Adzuna data

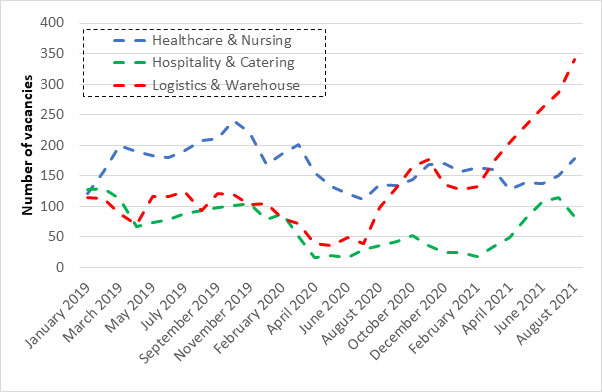

However, the pandemic has been experienced differently across different sectors and parts of the economy. Figure 2 provides an example of this by reporting on vacancies in healthcare and nursing, hospitality and catering, and logistics and warehouse work. As would be expected healthcare vacancies have remained relatively more stable throughout the pandemic, with less pronounced declines or growth in response to lockdowns. On the other hand, vacancies in the hospitality sector feel precipitously as venues closed, remaining relatively depressed for a year before recovering to somewhere around pre-pandemic levels in summer 2021. The logistics and warehousing sector shows a different pattern again. Although the sector experienced a pandemic dip, this was more short-lived, with a following period of rapid growth punctuated by a brief dip in response to the subsequent lockdowns. By the summer of 2021, vacancy figures in logistics and warehousing were around three times higher than pre-pandemic numbers. This high growth is likely to be partly driven by some of the consumption changes which sped-up during the pandemic and which look persistent – with more internet shopping and home deliveries – as well as the need to address wider supply-chain issues resulting from the pandemic and other factors.

Figure 2: Advertised vacancies in health, logistics and hospitality sectors: Wolverhampton, 2019-2021

Source: Author Analysis of Adzuna data

Business and management implications

Local vacancy trends have important implications for employers. Changes in vacancies in other parts of the economy can mean firms have to increase salaries to compete. Nationally, Pret A Manger have recently raised pay rates twice in six months to try and attract workers in the context of recruitment shortages. In some sectors firms have offered signing-on bonuses or ‘Golden Hellos’ as high vacancy levels reflect a shortage of labour (workers) or skills. These shortages can have implications for growth in the both the short and long-term (for example if there is a shortage of bricklayers’ then developments proceed more slowly, while a shortage of digital skills can reduce innovation).

Next steps

The charts above provide a top-line and the overall trends in a particular city. However, the vacancy data also provide the opportunity for much more detailed analysis of sectors and pay, and allows for comparison between different types of places (different cities and towns, city centres and suburbs, urban and rural). These are issues which we will be examining as part of our current research project on ‘Growth, resilience and recovery in local and city economies’.

-ends-

Notes: This project has been facilitated by the Urban Big Data Centre at Glasgow University. The work is in collaboration with Professor Donald Houston (University of Portsmouth). Information about the geographic location of individual vacancies are used to map them to the local authority area. The data used is: Adzuna. Economic and Social Research Council. Adzuna Data, 2022 [data collection]. University of Glasgow - Urban Big Data Centre

By Professor Paul Sissons, Head of the Management Research Centre, University of Wolverhampton Business School

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/iStock-163641275.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/250630-SciFest-1-group-photo-resized-800x450.png)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/210818-Iza-and-Mattia-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images/Maria-Serria-(teaser-image).jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/241014-Cyber4ME-Project-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/210705-bric_LAND_ATTIC_v2_resized.jpg)