Dr Dean-David Holyoake, Developmental Editor

Knowing what and how to review relates to knowing value when you see it. For example, Wetherspoons, double denim and mindless theorising. Yet, if I am correct that reviewing and value share some type of equation then you need look no further than this edition of JoHSCI. It has packs of both and what’s more, it’s free to everyone of curious disposition (and any other come to that). But that’s the thing about ‘reviewing’ as well as being about value. It’s also a way of life for academics. We view and then review and then start again in a never-ending chasm of noticing. I’m tempted to say searching, but that would not necessarily be correct unless of course, it’s for the afore mentioned pub. Now go view, value, re-review and enjoy.

Romantic love is viewed as a cross-cultural and intense experience that influences multiple aspects of human life (Jankowiak & Fischer, 1992, p. 149). Relationship quality, stability and relationship satisfaction are all said to be correlated with romantic love (Riehl-Emde et al., 2003, p. 266). While romantic relationships can lead to greater well-being, euphoria and longer life expectancy (Drefahl, 2012, p. 472), relationship dissolvement can lead to depression, anxiety, pain and acute mental distress (Mearns, 1991, p. 328). Additionally, the Office for National Statistics in the UK, recorded the highest number of opposite-sex couple divorces in 2019, which was an increase of 18.4% compared to the 90,871 divorces that took place in 2018 (Ghosh, 2020). The most common grounds for divorce for opposite-sex couples was “unreasonable behaviour” with 49% of wives and 35% of husbands petitioning on these grounds (Ghosh, 2020). Consequently, Psychologists have an important role to play when counselling couples, as the effectiveness of therapy could impact not only the couples, but also their children and future partners. The more information Counselling Psychologists have regarding the way men and women understand and communicate love, the more effective therapy may become.

Some scientists argue that these divergences in behaviours and opinions may be due to gender differences in cognitive processing (Yin et al., 2013). Cognitive processes encompass almost all basic, as well as complex mental manipulation or storage of information (Spicer & Ahmad, 2006, p. 221). This includes memory, decision-making, learning, language use, reasoning and problem-solving (Smith & Kelly, 2015, p. 2). Over the years there have been many studies establishing gender differences in cognitive processing (Theofilidis et al., 2020, p. 269; Wehrwein et al., 2007, p. 156). Early studies found that men and women differed in their conceptualisation of love such that men are more likely to think about sexual commitment and intercourse satisfaction when thinking about love, while women are more likely to think of emotional commitment (Buss, 1988; 2000).

However, not many studies have explored the consequences of these cognitive differences in relation to romantic relationships. Yin et al., (2013) is one of the few studies which has sought to understand how romance is identified and assessed in a romantic relationship. The results of the study provide the first piece of evidence for gender differences in romance perception, proposing that it is more effortful for men to perceive and evaluate romance. Furthermore, results showed higher rating scores in males than females for low romance items, but not for high or medium romance items. This can explain how men might perceive simpler acts as romantic, while women see these same gestures or scenarios as low romance or normal day-to-day occurrences, leading women to feel like men are not romantic enough. In addition to the evidence of gender differences in romantic information processing, there is also evidence that the way love and romance is conceptualised and perceived can be influenced by gender. A further study by Yin et al., (2018) investigating romantic appraisals in male and female Chinese college students, found that men and women differed in the processing of romantic information and that it may be more effortful for men to perceive and evaluate romance degree (Yin et al., 2018).

Although both studies by Yin et al. (2013, 2018), provide unique evidence proposing gender differences in romance perception, the studies were conducted using only Chinese students. Cultural psychologists have already established that eastern and western cultures have significant differences in how romantic love is experienced and valued. Notably US couples are found to be significantly more passionate than Chinese couples (Gao, 2001). Therefore, it would be useful to conduct similar studies using western participants. Furthermore, although they show that there are indeed gender differences in the processing of romantic information and romance perception, it does not evaluate whether it influences how people experience felt love or the greater impact it may have in romantic relationships.

These limitations are explored by Oravecz et al., (2016), who not only produced a more Westernised study, since it was based in the United States of America (US), but also interpreted love as a form of communication and explored specific scenarios that evoked felt love. Using cultural consensus theory to generate information, a group of lay participants were asked to generate descriptors of felt love situations, after which a second participant group rated these same situations according to what made them feel loved. Results proposed that there was a consensus on felt love. Furthermore, it was found that when women were faced with scenarios, they were uncertain of, they were more likely to judge those as indicators of felt love. This provides an area for potential exploration since perhaps it indicates that women are designed to maintain relationships which may have been a beneficial trait from an evolutionary perspective. Although the study was effective in conceptualising felt love as it occurs daily, and exploring whether there was a felt love consensus, the study was interested in all manifestations of felt love, not specifically romantic relationships. As such many items on the felt love questionnaire were irrelevant to romantic love (e.g., religion: does being closer to god make you feel loved?). Perhaps different results would be observed if the questionnaire was focused on felt romantic love. Furthermore, although the study was conducted in America, social norms are still different to the United Kingdom (UK) (e.g., people are said to be less religious that in America) (Furman et al., 2005).

Oravecz et al. (2016) study was further explored by Heshmati et al., (2017) and gained more detailed information on individual differences within the subject area. Results indicated that male participants lacked knowledge on experiences which elicited felt love compared to women. Meaning they were more uncertain about which actions evoked felt love. Therefore, it would be beneficial for future studies to consider gender differences while conducting cultural consensus analysis, before deciding which items should be used in a “felt love consensus” questionnaire. Hopefully, this will ensure greater understanding about what makes both men and women feel loved. Furthermore, there is a need for further investigation using people living in the UK, to provide a more representative consensus of felt love, since it is already known that there are major cultural differences when it comes to romance perception (Gao, 2001). Lastly the current felt love questionnaire created by Oravecz et al., (2016) is not specific to romantic relationships, indicating a need for a more accurate and valid measure, as well as being more targeted towards a UK sample.

Currently, there are several psychological therapies and interventions used to enhance relationship satisfaction and treat relational difficulties in romantic couples. Results from multiple studies have shown that integrative behavioural couples therapy, emotionally focused couples therapy, couples-focused cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural couples therapy are particularly effective (Halford & Snyder, 2012; Sexton & Alexander, 2003). Nonetheless, effect sizes found in effectiveness studies are only moderate and effect-sizes in naturalistic, real-world settings are significantly lower than in controlled study conditions. In addition, it is still unknown how and why these therapies are useful, especially since there is no improvement in up to 50% of couples (Roesler, 2019). This indicates that more knowledge is needed to improve therapeutic outcomes and to understand why therapy works for some and not for others. Counselling psychologists adopt a pluralistic and integrative philosophy, meaning no single intervention is favoured. Therefore, further exploration in the field can allow counselling psychologists to identify the different components from various interventions, which led to improvements; thus, facilitating the integration of therapies. Hopefully, by identifying the effective components from these different therapies, therapy can be refined to contain more evidence-based practices and reduce non-beneficial interventions.

References

Buss, D. M. (1988). Love acts: The evolutionary biology of love. In R. J. Sternberg &M. L. Barnes (Eds.), The psychology of love (pp. 100–118). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Buss, D. M. (2000). The evolution of happiness. American Psychologist, 55, 15.

Drefahl, S. (2012). Do the Married Really Live Longer? The Role of Cohabitation and Socioeconomic Status. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(3), 462–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00968.x

Furman, L. D., Benson, P., Canda, E., & Grimwood, C. (2005). A Comparative International Analysis of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work: A Survey of UK and US Social Workers. Social Work Education, 24(8), 813–839. https://doi-org.ezproxy.wlv.ac.uk/10.1080/02615470500342132

Gao, G. (2001.) Intimacy, passion and commitment in Chinese and US American romantic relationships. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 25: 329–342.

Ghosh, K. (2020, November 17). Divorces in England and Wales - Office for National Statistics [Dataset]. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/divorce/bulletins/divorcesinenglandandwales/2019

Halford, W. K., & Snyder, D. K. (2012). Universal processes and common factors in couple therapy and relationship education. Behaviour Therapy, 43, 1 – 12.

Heshmati, S., Oravecz, Z., Pressman, S., Batchelder, W. H., Muth, C., & Vandekerckhove, J. (2017). What does it mean to feel loved: Cultural consensus and individual differences in felt love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(1), 214–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517724600

Jankowiak, W. R., & Fischer, E. F. (1992). A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Romantic Love. Ethnology, 31(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773618

Mearns, J. (1991). Coping with a breakup: Negative mood regulation expectancies and depression following the end of a romantic relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 327–334. https://www.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.327

Roesler, C. (2019). Effectiveness of Couple Therapy in Practice Settings and Identification of Potential Predictors for Different Outcomes. Family Process, 59(2), 390–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12443

Sexton, T. L., & Alexander, J. F. (2003). Functional family therapy: A mature clinical model for working with at-risk adolescents and their families. In T. L. Sexton, G. R. Weeks, & M. S. Robbins (Eds.), Handbook of family therapy: The science and practice of working with families and couples (pp. 323–348). Brunner-Routledge

Smith, A. D., & Kelly, A. (2015). Cognitive Processes. The Encyclopedia of Adulthood and Aging, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118521373.wbeaa213

Smith, A. D., & Kelly, A. (2015). Cognitive Processes. The Encyclopedia of Adulthood and Aging, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118521373.wbeaa213

Spicer, D. P., & Ahmad, R. (2006). Cognitive processing models in performance appraisal: evidence from the Malaysian education system. Human Resource Management Journal, 16(2), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2006.00007.x

Theofilidis, A., Karakasi, M.-V., Kevrekidis, D.-P., Pavlidis, P., Sofologi, M., Trypsiannis, G., & Nimatoudis, J. (2020). Gender Differences in Short-term Memory Related to Music Genres. Neuroscience, 448, 266–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.08.035

Wehrwein, E. A., Lujan, H. L., & DiCarlo, S. E. (2007). Gender differences in learning style preferences among undergraduate physiology students. Advances in Physiology Education, 31(2), 153–157. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00060.2006

Yin, J., Zhang, J. X., Xie, J., Zou, Z., & Huang, X. (2013). Gender Differences in Perception of Romance in Chinese College Students. PLoS ONE, 8(10), e76294. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076294

Yin, J., Zou, Z., Song, H., Zhang, Z., Yang, B., & Huang, X. (2018a). Cognition, emotion and reward networks associated with sex differences for romantic appraisals. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21079-5

Correspondence:

University of Wolverhampton

A.Amesbury@wlv.ac.uk

Health Information and Anxiety

It is common for children to undergo a clinical procedure at some point during their childhood (Lindsey et al., 2013). However, current literature demonstrates that children find minor procedures very distressing (Carmichael 2015). Research has demonstrated that half of five-million children who underwent surgery developed significant anxiety beforehand (Kain et al., 2006). Minimising anxiety has important benefits and one way that is proven to do this is through the provision of health information prior to a procedure.

Information about a procedure can reduce children’s anxiety around what is going to happen and facilitate realistic expectations (Bray et al., 2019a). Furthermore, literature suggests that children feel empowered when provided with this information (Ben Ari et al., 2019). Additionally, children are more likely to have poor experiences if they are not suitably prepared for procedures (Sheehan et al., 2015) and higher levels of anxiety (Carmichael et al., 2014) which can result in missed follow-up appointments (Shahnavaz et al., 2015), delays in recovery (Kerimoglu et al., 2013) and fear of medical professionals (Mahoney et al., 2010). This suggests that inadequate preparation can result in poor health outcomes and have other long-term psychological impacts, highlighting the importance of research in this area. Despite this, many children report that they have not accessed any health information prior to coming to hospital for a procedure. Additionally, limited time with professionals can act as a barrier to parents feeling adequately prepared (Bray et al., 2019a).

It is not only children who are negatively affected by feelings of anxiety when undergoing medical interventions, but parents also commonly experience anxiety (William Li et al., 2007). Furthermore, parent’s level of anxiety is positively correlated with their child’s level of anxiety (LaMontagne et al., 2001; Li & Lam, 2003) which suggests it may be important to support parents in managing their anxiety to help reduce children’s anxiety. The results of one study suggested parents derive benefits from child preparation programmes; parents who accompanied their child to a preoperative preparation group showed lower levels of anxiety compared to those who did not (Fincher et al., 2012). This highlights the importance of parental involvement in preoperative preparation for children and points towards a family-centred care approach (Li & Lopez, 2008).

Views of Parents and Children

Alongside the empirical evidence demonstrated, qualitative studies exploring the views of parents and children have shown that there is a desire for pre-procedural information. In a recent study, children explained that procedural information supports them to be aware of what is going to happen and feel less scared about a medical intervention (Bray et al., 2019b). Children also reported that they felt this information would enable them to practice coping strategies to help them to get through the procedure (Hockenberry et al., 2011). In addition, research states that both parents and health professionals feel that this information would be helpful for children. Despite this, parents report not sharing this information with their children (Bray et al., 2019a). Literature has suggested that future research is required to examine factors that influence parent’s decisions to share or withhold pre-procedural information (Ben Ari et al., 2019).

Parents as Gatekeepers

Research shows that when accessing procedural information children are often reliant on their parents (Bray et al., 2019a). However, despite parents reporting that pre-procedural information would be helpful for children, a recent study explained that parents reported they had either not received information or had not read or communicated the information if they had received it, “When we are given leaflets they just go to the bottom of my bag and I forget about them” (Bray et al., 2019a, p.631). It is not clear why this information was not passed on to children (Bray et al., 2019a). However, parents are unintentionally disempowering their children when they limit access to this information (Birnie et al., 2014). It is clear that further research is needed in this area to support parents to share health information with their children, which could reduce anxiety prior to medical procedures.

Limitations of Current Research

Literature demonstrates that age influences perioperative anxiety in children (Ahmed et al., 2011) and suggests that participants in different age groups may express pain or anxiety differently (He et al., 2015). However, current research spans across different age ranges and does not appear to acknowledge the impact that age-related differences could have on findings. Therefore, future studies exploring pre- and post-procedural information on anxiety should both examine and take into account age-related individual differences.

Another possible limitation of current research is that many outcome measures were based on subjective self-reports. Therefore, responses of children and parents could have been influenced by demand characteristics or subjective interpretation of questions. Future studies could incorporate reliable measures such as the State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children which is considered the ‘gold standard’ in measuring anxiety in children over 5 years old (Ahmed et al., 2011) to increase the reliability and validity of results. In addition, more objective outcome measures such as blood pressure, cortisol levels and heart rate could also be used to verify self-report findings in future research (He et al., 2015).

Research Gap

Positively, research has been conducted into the views of parents, children and professionals in regard to children accessing health information prior to a procedure. However, to the author's knowledge, there is a gap in research looking into why parents may be reluctant to share this information with their child despite parents explaining that pre-procedural information would be useful in reducing anxiety (Bray et al., 2019a). Therefore, further research is needed to explore why parents’ may not share this information with their children. Parents could act as either facilitators or barriers for their children in the receipt of information to help prepare them for health interventions. Therefore, identifying possible barriers and areas where further support is needed could facilitate access to health information for more children prior to a procedure and reduce anxiety and negative long-term effects.

References

Ahmed, M. I., Farrell, M. A., Parrish, K., & Karla, A. (2011). Preoperative anxiety in children risk factors and non- pharmacological management. Middle East Journal of Anesthesiology, 21(2), 153-164.

Ben Ari, A., Margalit, D., Roth, Y., Udassin, R., & Benarroch, F. (2019). Should parents share medical information with their young children? A prospective study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 88, 52-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.11.012

Birnie, K., Noel, M., Parker, J., Chambers, C., Uman, L., Kisely, S., & McGrath, P. (2014). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Distraction and Hypnosis for Needle-Related Pain and Distress in Children and Adolescents. Journal Of Pediatric Psychology, 39(8), 783-808. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsu029

Bray, L., Appleton, V., & Sharpe, A. (2019a). ‘If I knew what was going to happen, it wouldn’t worry me so much’: Children’s, parents’ and health professionals’ perspectives on information for children undergoing a procedure. Journal Of Child Health Care, 23(4), 626-638. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493519870654

Bray, L., Appleton, V., & Sharpe, A. (2019b). The information needs of children having clinical procedures in hospital: Will it hurt? Will I feel scared? What can I do to stay calm?. Child: Care, Health And Development, 45(5), 737-743. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12692

Carmichael, N., Tsipis, J., Windmueller, G., Mandel, L., & Estrella, E. (2015). “Is it Going to Hurt?”: The Impact of the Diagnostic Odyssey on Children and Their Families. Journal Of Genetic Counseling, 24(2), 325-335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-014-9773-9

Fincher, W., Shaw, J., & Ramelet, A. (2012). The effectiveness of a standardised preoperative preparation in reducing child and parent anxiety: a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Journal Of Clinical Nursing, 21(7-8), 946-955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03973.x

He, H., Zhu, L., Chan, S., Klainin-Yobas, P., & Wang, W. (2015). The Effectiveness of Therapeutic Play Intervention in Reducing Perioperative Anxiety, Negative Behaviors, and Postoperative Pain in Children Undergoing Elective Surgery: A

Systematic Review. Pain Management Nursing, 16(3), 425-439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2014.08.011

Hockenberry, M., McCarthy, K., Taylor, O., Scarberry, M., Franklin, Q., Louis, C., & Torres, L. (2011). Managing Painful Procedures in Children With Cancer. Journal Of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 33(2), 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1097/mph.0b013e3181f46a65

Kain, Z., Mayes, L., Caldwell-Andrews, A., Karas, D., & McClain, B. (2006). Preoperative Anxiety, Postoperative Pain, and Behavioral Recovery in Young Children Undergoing Surgery. Pediatrics, 118(2), 651-658. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2920

Kerimoglu, B., Neuman, A., Paul, J., Stefanov, D., & Twersky, R. (2013). Anesthesia Induction Using Video Glasses as a Distraction Tool for the Management of Preoperative Anxiety in Children. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 117(6), 1373-1379. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e3182a8c18f

LaMontagne, L., Hepworth, J., & Salisbury, M. (2001). Anxiety and postoperative pain in children who undergo major orthopedic surgery. Applied Nursing Research, 14(3), 119-124. https://doi.org/10.1053/apnr.2001.24410

Li, H., & Lam, H. (2003). Paediatric day surgery: impact on Hong Kong Chinese children and their parents. Journal Of Clinical Nursing, 12(6), 882-887. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00805.x

Li, H., & Lopez, V. (2008). Effectiveness and Appropriateness of Therapeutic Play Intervention in Preparing Children for Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial Study. Journal For Specialists In Pediatric Nursing, 13(2), 63-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2008.00138.x

Lindsey, M., Brandt, N., Becker, K., Lee, B., Barth, R., Daleiden, E., & Chorpita, B. (2013). Identifying the Common Elements of Treatment Engagement Interventions in Children’s Mental Health Services. Clinical Child And Family PsychologyReview, 17(3), 283-298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0163-x

Mahoney, L., Ayers, S., & Seddon, P. (2010). The Association Between Parent’s and Healthcare Professional’s Behavior and Children’s Coping and Distress During Venepuncture. Journal Of Pediatric Psychology, 35(9), 985-995. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsq009

Shahnavaz, S., Rutley, S., Larsson, K., & Dahllöf, G. (2015). Children and parents’ experiences of cognitive behavioral therapy for dental anxiety - a qualitative study. International Journal Of Paediatric Dentistry, 25(5), 317-326. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12181

Sheehan, A., While, A., & Coyne, I. (2015). The experiences and impact of transition from child to adult healthcare services for young people with Type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetic Medicine, 32(4), 440-458. https://doi.org/10.1111/me.12639

William Li, H., Lopez, V., & Lee, T. (2007). Effects of preoperative therapeutic play on outcomes of school-age children undergoing day surgery. Research In Nursing & Health, 30(3), 320-332. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.

Correspondence:

University of Wolverhampton

S.E.Halls@wlv.ac.uk

In the UK, health care is the responsibility of the national government while social care is mediated by the local authority. Social care services oversee the running of residential and nursing homes, referred collectively from now on as care homes. It is estimated that there are over 416,000 residents living in

UK care homes (Laing, 2016) with this number set to rise (Bone et al., 2018). Care home residents are typically the most vulnerable and frail of the population and are often unable to live independently. It is also evidenced that these individuals have comorbid health problems and frequently need access to a wide range of health and social care services. It is therefore interesting that individuals living within a care home setting are actively excluded from research trials, making them a marginalised group (Backhouse et al., 2016).

Research in care home settings is ‘behind the curve’ compared to other populations (Moore et al., 2019). This is worrying as the literature suggests that care homes are generally underserved and under resourced (Paddock et al., 2019) and these issues cannot be resolved without research and a strong evidence base on which to ground change on. There have been numerous initiatives to integrate both health and social care, with limited success (Exworthy, Powell, and Glasby, 2017). From personal experience of working on the front line of the NHS to now conducting research within the health and social care sector, I believe the lack of research opportunities for care home residents and staff need to be addressed. As research drives practice, policy making and commissioning decisions, research projects need to stop excluding care home populations and justifications for exclusions should be scrutinised by Research Ethics Committees. Moreover, further research will increase our knowledge about the needs of care homes which may further elicit successful attempts for the integration of health and social care services.

One barrier for including care home residents and staff in research is the need for researchers to be extremely flexible. Care homes are busy environments and research will never be a main priority.

The current project I am working on is collaborating with care homes and it is challenging to organise meetings with keen senior care home staff due to the extreme pressures they are under. This experience is not an isolated incident and the National Institute of Health Research’s (NIHR) ENRICH toolkit offers guidance on how to overcome some of these common barriers.

The purpose of this opinion piece is to make researchers aware of the need to include care home residents and staff in health and social care research and to highlight the need for more education and guidance around this topic.

References

Backhouse, T. et al. (2016) ‘Older care-home residents as collaborators or advisors in research: a systematic review’, Age and Ageing, 45(3), pp. 337–345.

Bone, A. E. et al. (2018) ‘What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care?

Population-based projections of place of death’, Palliative Medicine, 32(2), pp. 329–336.

Exworthy, M., Powell, M. and Glasby, J. (2017) ‘The governance of integrated health and social care in England since 2010: great expectations not met once again?’, Health Policy, 121(11), pp. 1124–1130.

Laing, W., (2016). Care of Older People. Market Report. 27th Edition. London: Laing and Buisson.

Moore, D. C. et al. (2019) ‘Research, recruitment and observational data collection in care homes: Lessons from the PACE study’, BMC Research Notes, 12(1), p. 508.

Paddock, K. et al. (2019) ‘Care Home Life and Identity: A Qualitative Case Study’, The Gerontologist, 59(4), pp.

655–664.

Correspondence:

Falmouth University

Jacob.brain@falmouth.ac.uk

Abstract

Introduction: As life expectancy worldwide is increasing, the prevalence of frailty is also on the rise. This scoping review aimed to identify and collate published information relating to frailty and spousal/partner bereavement in older people.

Method: A scoping review framework was used to identify papers that discussed frailty and spousal/partner bereavement. For example, the death of a life partner whether married or unmarried co-habiting, in community dwelling and individuals aged 60+ years old, were included.

Results: Four studies were included. Overall, spousal/partner bereavement was negatively associated with the incidence and level of frailty. All four studies reported that elderly widowed females had a higher prevalence of frailty compared to married females and widowed and/or married males. Males were also less likely to be widowed or living alone compared to females. Female longevity and the potential of living alone once bereaved increases the risk of frailty for this population.

Discussion: This review identifies the needs of ageing populations and the potential risk of frailty associated with spousal/partner bereavement.

Conclusion: This review helps make nurses more aware of the possible impact of bereavement on the development of frailty in older people and identify those most at risk, and/or in need of specific support/interventions.

Keywords: Frailty, ageing, aging, widowhood, bereavement, risk

What is known and what this paper adds:

- This review summarises the sparse but existent evidence base on frailty in bereaved spouses/partners

- The review highlights the need to apply a clear operational definition for frailty

- The results help nurses gain an understanding of the physical and psychological signs of frailty in older adults

- This paper highlights the factors that may contribute to frailty following bereavement

- More research is needed to understand the factors which may mediate the development of frailty following bereavement

- The paucity of results highlights the need for further studies

Introduction

Life expectancy is increasing (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, 2017), as data from the World Health Organisation indicate that 900 million people are aged over 60 (12% of global population) and this is predicted to increase to 2 billion (22% of the global population) by 2050 (The World Health Organisation, 2020). Typically, older age is correlated with increased health-related problems and becoming frailer (Kojima, Liljas and Iliffe, 2019). It is estimated that one quarter of people over 85 years are frail and have significantly increased risk of falls, disability, long-term care and death (Fried et al., 2001; Song, Mitnitski and Rockwood, 2011, Buckinx et al., 2015). In the United Kingdom (UK), it is projected that by 2036, over half of all local authorities will have 25% or more of their local population aged 65 and over (Office for National Statistics, 2017).

Growing interest in frailty research has attempted to provide an improved understanding of the heterogeneous factors that may contribute to the onset of frailty (Clegg et al., 2013). Currently, there is no agreed operational definition for the syndrome known as ‘frailty’ nor agreed diagnostic criteria (Hogan, 2006; Bergman et al., 2007; Buckinx et al., 2015). Frailty is an ambiguous term; however, it commonly refers to an increased vulnerability to adverse health outcomes when exposed to stressors (either internal or external) (Clegg et al., 2013).

In 2016, a WHO consortium defined frailty as “a clinically recognisable state in which the ability of older people to cope with everyday or acute stressors is compromised by an increased vulnerability brought by age-associated declines in physiological reserve and function across multiple organ systems” (WHO Clinical Consortium on Healthy Ageing, 2017). Frailty is also used as a prognostic indicator (RCP, 2020). For example, in the COVID-19 pandemic, frailty has been used to identify those at higher risk of poor outcomes (RCP, 2020).

The two most frequently used frailty definitions and assessment tools are the frailty phenotype (Kojima, Liljas and Iliffe, 2019) (also known as Fried’s definition or Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) definition) and the frailty index (FI) (Jones, Song and Rockwood, 2004). The frailty phenotype classifies frailty as a syndrome that has three or more of five phenotypic criteria: weakness as measured by low grip strength, slowness by slowed walking speed, low level of physical activity, low energy or self-reported exhaustion, and unintentional weight loss. Pre-frailty is defined as having one or two criteria present. Non-frail older adults are classified as having none of the above five criteria. The frailty index is a measure of the number of ‘deficits’ identified during a comprehensive geriatric assessment, including diseases, physical and cognitive impairments, psychosocial risk factors, and common geriatric syndromes other than frailty (Jones, Song and Rockwood, 2004; Searle et al., 2008). Variables are identified as meeting the FI inclusion deficit criteria if the ‘deficit’ is acquired, is age-associated, is associated with an adverse outcome, and should not saturate too early (Jones, Song and Rockwood, 2004; Searle et al., 2008; Leng, Chen and Mao, 2014).

Due to the predicted increase of individuals living into older age, and the potential subsequent increase of frail older adults, it is essential that the predictive characteristics of the syndrome, including factors that may impact onset, are better understood. For example, while frailty is most commonly identified in older adults, frailty is not determined by old age (Schuurmans et al., 2012). Frailty is a spectrum syndrome that can encompass a myriad of environmental, psychological and physiological impairments (Gobbens et al., 2010). Furthermore, several sociodemographic variables have been associated with frailty, including age and gender (Grden et al., 2017). Haapanen (2018) and colleagues reported that frailty is, in part, programmed in early life and is associated with lower socioeconomic status in adulthood (Haapanen et al., 2018). Regarding later life, there is extensive research demonstrating a negative impact of widowhood on health outcomes. These impacts include a higher risk of disability (Goldman, Korenman and Weinstein, 1995), higher rates of depression and psychological distress (Gove, 1975; Pearlin and Johnson, 1977) and increased mortality rates in separated individuals compared to married individuals (Gove, 1975).

Research examining the relationship between marital status, specifically widowhood, and frailty is limited (Trevisan et al., 2016). Whilst a large body of research has examined the various psychological and physiological complications which may be associated with spousal loss, such as cardiovascular outcomes (e.g. Ennis and Majid, 2019), this scoping review focuses specifically on studies where a specific frailty definition was applied, in order to provide a more focused and clinically-informed review.

While frailty appears to affect females more than males, Trevisan and colleagues (2016) assessed a combined community dwelling and nursing home population sample, reporting that widowed or single males have a higher risk of developing frailty compared to married males, whereas widowed women carry a significantly lower risk of becoming frail compared to married women. The same authors identified unintentional weight loss, low daily energy expenditure, and exhaustion as factors associated with marital status and linked to related caring responsibilities which contributed to frailty (Trevisan et al., 2016). Studies have also identified gender-specific differences in marital status, mortality and psychological wellbeing, showing an increased risk for divorced, single, widowed or never married males compared to females (Gove, 1975; Pearlin and Johnson, 1977; Hu and Goldman, 1990; Trevisan et al., 2016). Despite an association between marital status and healthy ageing being reported, little is known about the relationship between spousal/partner bereavement (i.e. the death of a life partner whether married or unmarried co-habiting) in community dwelling populations and frailty.

The aim of this review is to identify studies which examine the impact of partner/spousal bereavement on the development of frailty in older people living in community settings

Methods

Study design

A scoping method was used as initial searches revealed a paucity of pre-identified published studies, but nonetheless it was appropriate to identify and summarise this sparse literature (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). It was anticipated that the current literature would be methodologically heterogenous and for this reason, the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and the guidelines for best practice provided by Colquhoun et al. (2014) were implemented, in addition to the PRISMA-ScR (Tricco et al., 2018) to support a more rigorous and systematic approach. The Arksey and O’Malley’s framework consists of six stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarising and reporting results and (6) consultation with stakeholders. The optional final stage, consultation, was not included in the current scoping review, as this review was intended for publication to disseminate findings. Stages 1-5 are discussed below.

Stage 1: identifying the research question

This review aims to address the following questions:

- Is there a relationship between spousal/ partner bereavement and frailty?

- What factors influence frailty in bereaved older adults (60+) (protective or other)?

- What interventions are available, within the UK and internationally, that prevent any impact of spousal/partner bereavement, resulting in frailty?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

An initial exploratory online search using the electronic databases MEDLINE (PubMed) and CINAHL identified a paucity of articles and evaluation reports related to the topic of spousal/ partner bereavement and frailty. Next, the words in the title and abstract of relevant retrieved papers were then analysed in addition to the index terms used to describe the articles. These combined terms were used to form the keywords and index terms (see Appendix 1) for the systematic search strategy that was undertaken across all specified databases. Databases were searched from their start dates to April 2020 and searches were re-ran in June 2020 to make sure no new relevant new literature was overlooked.

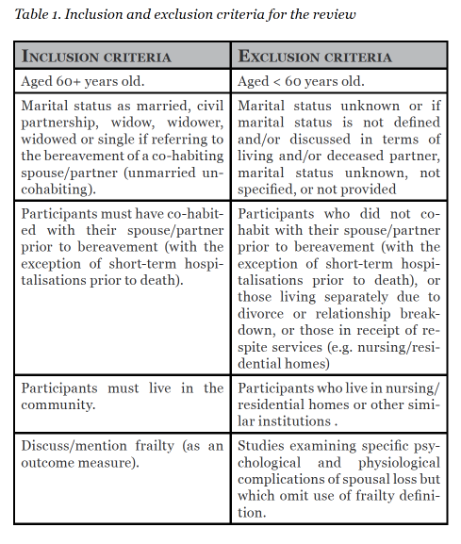

Databases used were CINAHL, British Nursing Index, Web of Knowledge, Cochrane library, PsychInfo, SocIndex, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (DARE, NHS EED, HTA), JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, MEDLINE, EPPI, Epistemonikos, grey literature and references of included studies. Google Scholar citations of identified reports and articles were also searched for additional studies. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. The review was international in scope; however, only English language studies were included.

Stage 3: study selection

Initial screening selection (title and abstract screening) was distributed amongst four reviewers, divided into two groups. This was undertaken to measure inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) in the study selection part of the review, aiming to add a new dimension to scoping reviews. Each group screened the full initial screening selection, with hits divided amongst both reviewers in each group. The screening selection for reviewer one from group A was paired with reviewer one from Group B and similarly for reviewer two from group A and reviewer two from Group B.

After eliminating the duplicates (studies that were identified more than once by the search engines), an initial screening of titles, abstracts, and summaries (if applicable) was undertaken to exclude records that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. Each record was classified as ‘include’ or ‘exclude’ to identify relevant, and exclude irrelevant, literature. The researchers were inclusive at this stage and, if uncertain about the relevance of a publication or report, it was left in. Any disagreements in studies shortlisted for full text screening were solved by consensus or by the decision of a fifth reviewer, where necessary.

Shortlisted study selection (full text screening) was then performed by four reviewers

- Any disagreements were solved by consensus or by the decision of a fifth reviewer where necessary. The agreement between the reviewers was again assessed with Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ), for both sets of paired reviewers.

- Devkota and colleagues (2017), Grden et al. (2017) and Gross et al. (2018) found that living with a family member as opposed to a spouse can indicate greater frailty risk. On the other hand, Grden and colleagues (2017) argue that living with a family member can create a type of dependency, whether financial, physical and/or psychological, which may accelerate or contribute towards

The full text was obtained for all the records that potentially met the inclusion criteria (based on the title and abstract/summary only), as agreed by all reviewers. In this second step, all the full text papers were screened against the inclusion criteria, using a standardised tool. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were listed with the reasons for exclusion. Multiple publications and reports on the same interventions were linked together and compared for completeness. The record containing the most complete data on any single intervention was identified as the primary article in the review, which was usually the original study or most recent evaluation report. A total of four studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Stage 4: charting the data

Data (or study findings) for analysis were extracted from the included studies and managed in an Excel spread sheet. The data extraction sheet was tested on three included papers and, where necessary, it was revised to ensure it could be reliably interpreted and would capture all relevant data from different study designs. Extracted data included authors; year of study/report; aim/ purpose; type of paper (e.g. journal article, annual evaluation report etc); country/location; study population (e.g. age of participants, gender, marital status, living arrangements, health status pre- bereavement); average length of relationship (in years); average length of bereavement (in years); sample size; study design; frailty definition/ criteria; frailty rate; factors that impact on frailty rate (protective and negative factors); description of any interventions/support for study population; description of the interventions/support (if any); factors that facilitate and/or hinder access to interventions/support (if any) and any key findings that related to the review questions.

Stage 5: Collating, Summarising and Reporting the Results

A narrative synthesis was implemented to identify the main outcomes from the included studies, and findings were recorded using an Excel spreadsheet.

Results

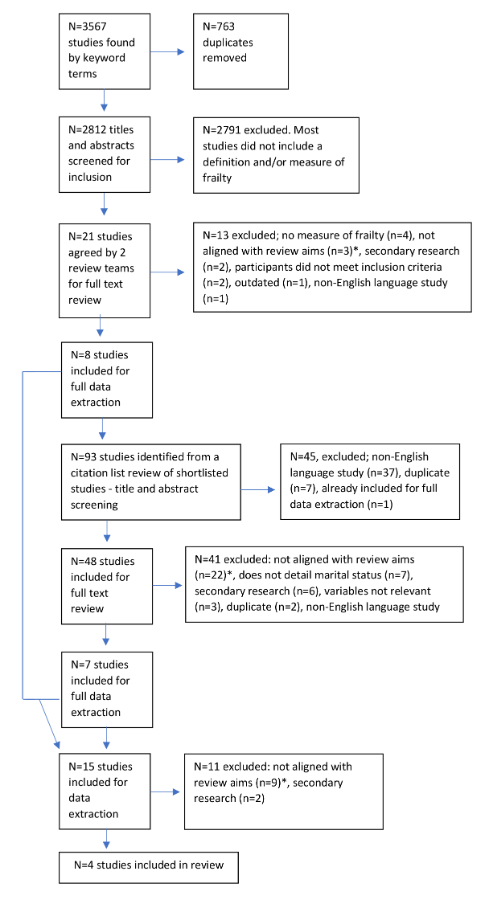

Initial screening (title and abstract) of 2812 records was completed independently by four reviewers (removed for review). Reviewers were divided into two groups, agreement was made between group 1 reviewers, assessed with the Cohen’s kappa (k)= 0.25 (fair agreement). The agreement between group 2 reviewers, assessed with the Cohen’s kappa (k)= 0.47 (moderate agreement). A fifth reviewer (JV) screened the initial shortlist of 91 records (title and abstract) and identified 21 records for possible inclusion. A full-text review of the 21 records was completed by all four reviewers (GB,KJ,RG,AM). Cohen’s kappa was not calculated at this stage, as three of the four reviewers could not access the full text of one or more papers. A fifth reviewer (JV) made the final decision regarding inclusion/exclusion where consensus could not be met. At the end of this review stage, eight records were identified that met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

The citation lists (as reported using Google Scholar) of the eight shortlisted inclusion papers were then screened by the five reviewers independently. Of these 93 records screened, seven records were identified that met the inclusion criteria, with the fifth reviewer making the final decision regarding inclusion/exclusion where consensus could not be met. At the end of this review stage, 15 further records were shortlisted for data extraction and inclusion in the review.

During full-text data extraction, a further eleven papers were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria when critically appraised.

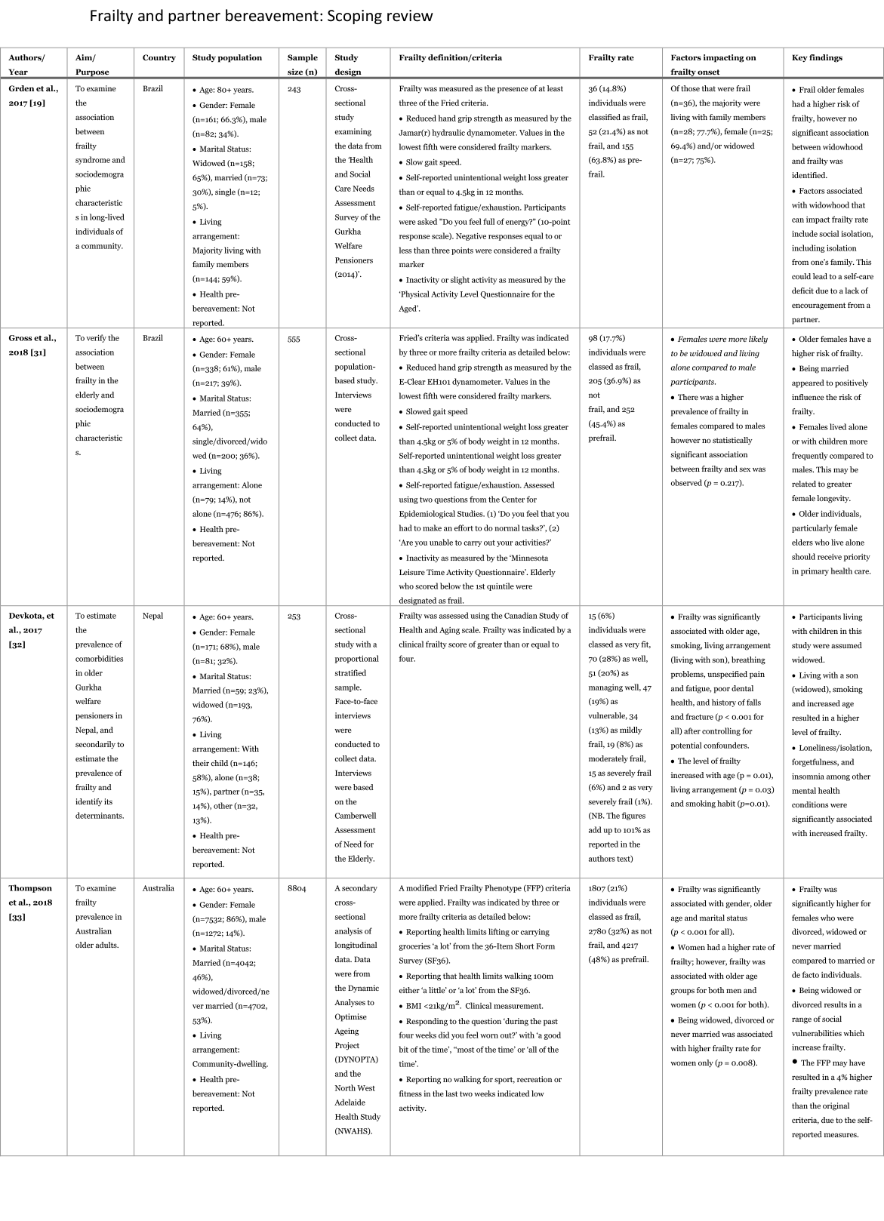

The final review included four research papers (Devkota et al., 2017; Grden et al., 2017; Gross et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2018) that met the inclusion criteria. The four studies were international in scope; Gardn et al. (2017) and Gross and colleagues (2018) were conducted in Brazil, Devkota et al. (2017) was undertaken in Nepal, and Thompson and colleagues (2018) was conducted in Australia. All four studies used cross-sectional designs, however, they implemented a variety of data collection methods, including survey (Gardn, et al., 2017), interviews (Gross, et al., 2018; Devkota, et al., 2017) and secondary analysis of quantitative data (Thompson, et al., 2018). All four papers had both male and female participants, although all studies had a higher number of female participants and the majority of participants were married, as opposed to being classified as a partner. Similarly, all four studies reported that the majority of participants were not living alone. The operational definition of frailty was varied across all four papers. Table 2 summarises the main characteristics and findings from the final included papers.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to identify studies which examine the impact of partner/spousal bereavement on the development of frailty in older people living in community settings. Specifically, the authors wanted to discern whether there was a relationship between bereavement and frailty, to identify what factors influence frailty in bereaved older adults and what interventions are available internationally (and in the UK) that may prevent the impact of partner bereavement resulting in frailty. All four studies (Devkota et al., 2017; Grden et al., 2017; Gross et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2018) identified that older females who were widowed, divorced, never married and/or living alone were at a greater risk of frailty compared to women who were married or when compared to their male counterparts. Of note, Grden and colleagues (2017) reported an increased rate of frailty with female widowhood but did not report a significant association. Of course, it is known that females generally have a higher rate of frailty compared to males (Davidson, DiGiacomo and McGrath, 2008; Collard et al., 2012; Buttery et al., 2015; Duarte and Paúl, 2015). However, caution must be applied when interpreting the relationship between frailty and bereavement as reported in the included studies for several reasons, not least due to the heterogeneous definitions of frailty used.

Further comparison in respect to spousal/ partner status was also problematic, due to variance in the way the studies reported marital status. For example, Gross and colleagues (2018) categorise individuals as single/divorced/widowed compared to married, whereas Thompson and colleagues (2018) categorise individuals as divorced/widowed/never married, compared to married/living with a partner. Additionally, it is unclear if any studies identify instances whereby widowed or unmarried individuals had partners or not. Moreover, identification of specific interventions in preventing frailty was not explicit in the identified studies, however, implicit mediators were identified and are discussed later in this paper.

An important consideration when interpreting the findings is that all four studies, aforementioned, included significantly more females compared to males. However, this is a common occurrence in aging research due to women living longer than men. This phenomenon has been referred to as the feminisation of aging (Davidson, DiGiacomo and McGrath, 2008; Gross et al., 2018) and refers to women outliving men on average for one to seven years. Yet, longevity does not always correspond to healthy life expectancy.

For example, increased longevity can result in more women living alone with potentially reduced support and fewer resources (Davidson, DiGiacomo and McGrath, 2008). All four study populations included in this review showed fewer women were reported as living with a spouse compared to men (Devkota et al., 2017; Grden et al., 2017; Gross et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2018).

In respect of factors that mediate frailty in older adults, the included papers found that women were more likely to live alone or with a family member, compared to men. Previous studies have reported that living with others can help maintain social relationships into older age resulting in better support networks, sustained health and the promotion of adaptive behaviour in stress the level of frailty experienced. Devkota and colleagues (2017) and Gross and colleagues (2018) note that the majority of their study participants were widowed females which may have resulted in this living arrangement. Similarly, Grden and colleagues’ (2017) found that 65% of participants were also widowed and 59% lived with a family member, as opposed to alone or with a spouse.

Furthermore, it should be noted that cultural practices of extended family living arrangements may also explain the findings of the included studies. Taken together, it is likely that marital status and living arrangements are interconnected, with marital status possibly influencing adjustments made to living arrangements following bereavement.

Inherent with the feminisation of aging is a greater prevalence of widowhood amongst women compared to men. This was reported in the studies included in the review, with more females being widowed, divorced or never married in all four studies (Devkota et al., 2017; Grden et al., 2017; Gross et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2018)]. Gross and colleagues (2018) suggest that being married may have protective effects, lowering the risk of frailty. They do not provide further details. Thompson and colleagues (2018) argue that being married appears protective against the social vulnerability variables associated with frailty, however, they do not expand further on this point. Conversely, Grden and colleagues (2017) did not find a statistically significant association between marital status and frailty, but they highlighted the social and familial isolation associated with widowhood, particularly the potential for a self-care deficit which might otherwise be counterbalanced by the encouragement of a partner.

Strengths and Limitations

The review had several strengths. It was systematic in its approach and was international in its scope. To provide a measure of inter-rater agreement, the review reported Cohen’s kappa coefficient (k) throughout each key stage. The review also included two separate pairs of reviewers to ensure that no potential studies were missed or excluded, and a fifth reviewer was available for when consensus could not be achieved. Additionally, this is the first paper, to the authors’ knowledge, that collates literature on frailty and spousal/partner bereavement.

Nevertheless, this review also has some limitations. Only a small number of papers met the inclusion criteria, suggesting that the impact of bereavement on older spouses/partners has not been given sufficient consideration in empirical research. It is recommended that future studies consider assessing widowhood in frailty studies and include widowhood or loss of a partner as an independent demographic within marital status. It is also suggested that researchers report the duration of both the relationship and time of bereavement in addition to living situation as these details should be recorded in future research.

Further, matched case-controlled designs would be useful to accurately identify trends in frailty between males and females, which cannot be assessed due to the over-representation of females in this scoping review. Due to the heterogenous definitions used for frailty and partner status, consensus is required in future research. This may have resulted in papers being excluded from this review at the final ‘data extraction’ stage. Finally, no papers included in this review implemented a longitudinal methodology whereby the impact of bereavement on frailty was measured over time. This is recommended for future studies.

Conclusion

While there is existing research examining marital status and frailty, further research is required to better understand the association between the bereavement of a partner/spouse and the onset of frailty, including the physical and psychological dimensions. In particular, the independent contribution of bereavement to frailty still needs to be identified. Based on the findings in this review, it is recommended that nurses are aware of the characteristics of frailty in older populations and the possible factors influencing the development of frailty in same, including a spouse or partner’s bereavement. In doing so, they may be able to intervene early and prevent the condition or reduce the level of severity. Considering the potential negative association between widowhood and being an older woman, it is suggested that nurses give particular consideration to how bereavement may affect the health status of older women who are now living alone. This may include directing them to community and voluntary organisations which provide bereavement support.

Declarations

Ethics approval not required.

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

This review was funded by the authors’ university.

References

Arksey, H. and O’Malley, L. (2005) ‘Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), pp. 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Bergman, H. et al. (2007) ‘Frailty: An emerging research and clinical paradigm - Issues and controversies’, Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. Gerontological Society of America, pp. 731–737. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.731.

Buckinx, F. et al. (2015) ‘Burden of frailty in the elderly population: Perspectives for a public health challenge’, Archives of Public Health. BioMed Central Ltd. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0068-x.

Buttery, A. K. et al. (2015) ‘Prevalence and correlates of frailty among older adults: Findings from the German health interview and examination survey’, BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), p. 22. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0022-3.

Clegg, A. et al. (2013) ‘Frailty in elderly people’, in The Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group, pp. 752–762. doi: 10.1016/ S0140-6736(12)62167-9.

Colquhoun, H. L. et al. (2014) ‘Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting’, Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Elsevier USA, pp. 1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013.

Davidson, P., DiGiacomo, M. and McGrath, S. (2008) The feminization of aging: how will this impact on health outcomes and services?

Devkota, S. et al. (2017) ‘Prevalence and determinants of frailty and associated comorbidities among older Gurkha welfare pensioners in Nepal’, Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 17(12), pp. 2493–2499. doi: 10.1111/ ggi.13113.

Duarte, M. and Paúl, C. (2015) ‘Prevalence of phenotypic frailty during the aging process in a Portuguese community’, Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia, 18(4), pp. 871–880. doi: 10.1590/1809-9823.2015.14160.

Ennis, J. and Majid, U. (2019) ‘“Death from a broken heart”: A systematic review of the relationship between spousal bereavement and physical and physiological health outcomes’, Death Studies. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2019.1661884.

Fried, L. P. et al. (2001) ‘Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype’, The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56(3), pp. M146–M157. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146.

Gobbens, R. J. et al. (2010) ‘Toward a conceptual definition of frail community dwelling older people’, Nursing Outlook, 58(2), pp. 76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.09.005.

Goldman, N., Korenman, S. and Weinstein, R. (1995) ‘Marital status and health among the elderly’, Social Science and Medicine, 40(12), pp. 1717–1730. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00281-W.

Gove, W. R. (1975) Sex, Marital Status, and Mortality, American Journal of Sociology. The University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.2307/2776709.

Grden, C. R. B. et al. (2017) ‘Associations between frailty syndrome and sociodemographic characteristics in long-lived individuals of a community’, Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 25. doi: 10.1590/1518- 8345.1770.2886.

Gross, C. B. et al. (2018) ‘Frailty levels of elderly people and their association with sociodemographic characteristics’, ACTA Paulista de Enfermagem, 31(2), pp. 209–216. doi: 10.1590/1982-0194201800030.

Haapanen, M. J. et al. (2018) ‘Early life determinants of frailty in old age: The Helsinki birth cohort study’, Age and Ageing, 47(4), pp. 569–575. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy052.

Hogan, D. B. (2006) ‘Models, Definitions, and Criteria of Frailty’, in Handbook of Models for Human Aging. Elsevier Inc., pp. 619–629. doi: 10.1016/B978-012369391-4/50051-5.

Hu, Y. and Goldman, N. (1990) ‘Mortality Differentials by Marital Status: An International Comparison’, Demography, 27(2), pp. 233–250. doi: 10.2307/2061451.

Jones, D. M., Song, X. and Rockwood, K. (2004) ‘Operationalizing a Frailty Index from a Standardized Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment’, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(11), pp. 1929–1933. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52521.x.

Kojima, G., Liljas, A. E. M. and Iliffe, S. (2019) ‘Frailty syndrome: Implications and challenges for health care policy’, Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. Dove Medical Press Ltd, pp. 23–30. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S168750.

Leng, S., Chen, X. and Mao, G. (2014) ‘Frailty syndrome: an overview’, Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, p. 433. doi: 10.2147/cia.s45300.

Office for National Statistics (2017) Overview of the UK population: July 2017. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/overviewoftheukpopulationjuly2017 (Accessed: 15 May 2020).

Pearlin, L. I. and Johnson, J. S. (1977) ‘Marital status, life-strains and depression.’, American sociological review, 42(5), pp. 704–715. doi: 10.2307/2094860.

Rose M. Collard et al. (2012) ‘Prevalence of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Persons: A Systematic Review - Collard - 2012 - Journal of the American Geriatrics Society - Wiley Online Library’, Journal of the American Geriatrics society. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x (Accessed: 15 May 2020).

Schuurmans, H. et al. (2012) ‘Old or Frail: What Tells Us More?’, The Journals of Gerontology, pp. 962–965. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/article/59/9/M962/535393 (Accessed: 15 May 2020).

Searle, S. D. et al. (2008) ‘A standard procedure for creating a frailty index’, BMC Geriatrics, 8(1), p. 24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-24.

Correspondence:

Rebecca Garcia1, Aoife Mahon2, Geraldine Boyle1, Kerry Jones1, Jitka Vseteckova1

1. Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies, The Open University, Buckinghamshire, UK

2. Adelphi Values, Patient-Centered Outcomes, Cheshire, UK

Supplementary materials

Figure 1: Flow chart showing included/excluded papers

Table 2. Summary of findings from the four papers that met the inclusion criteria.*

*Average length of relationship and average length of bereavement was not detailed in any study. No studies implemented interventions/support programmes.

A mixed-methods study assessing the relationship satisfaction and the mental health outcomes of perpetration and victimisation in Cyber Dating Abuse (CDA) among 18–20-year-olds

Cyber Dating Abuse (CDA) is defined as a form of digital abuse which occurs within romantic relationships and is conceptualised as multiple abusive behaviours such as surveillance (Bennett et al., 2011), control, harassment, threats (Zweig et al., 2014), humiliation (Hinduja & Patchin, 2011), hacking (Lucero et al., 2014), and revenge porn (Flach & Deslandes, 2017). CDA has been described as a multidimensional construct as it involves various typologies of abuse (Bennett et al., 2011).

Due to the strenuous demands of modern life and a decrease in mobility, online dating has gained enormous popularity among 18-25-year- olds (Frazzetto, 2010). Individuals are moving away from traditional methods of socialisation and opting for more practical methods (Finkel et al., 2012) that allows both instant connections and personal mobility (Lutz & Ranzini, 2017).

These developments have formed new avenues for dating youth to socialise; Zweig et al. (2014) found a significant percentage of online daters have experienced or perpetrated cyber-monitoring, cyberstalking, and other abusive behaviours. Those who have been victim to Child Domestic Abuse (CDA) are at risk of developing mental health difficulties (Eshelman & Levendosky, 2012) and low self-esteem (Göncü & Sümer, 2011). There is a growing body of evidence that states victims have low-levels of relationship satisfaction, while perpetrators have higher levels (Lancaster et al., 2019). However, research has suggested, young people may be prone to misinterpret CDA because of the distorted perception they have of love (Sharpe & Taylor, 1999) and it is more discreet than physical abuse (Temple et al., 2016). These unique characteristics can cause a discrepancy in the levels of relationship satisfaction for both victims and perpetrators of CDA, making CDA more detrimental than other types of dating abuse. This literature review explores the levels of relationship satisfaction and mental health implications of victims and perpetrators in CDA within the existing literature, whilst highlighting the study’s rationale.

Several studies have found an alarming number of college students who have been involved in some form of CDA in their relationships. Burke et al. (2011) found 50% out of a sample of 804 college students, had experience of CDA. Caridade et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review and reported the rates of victimisation and perpetration within young adults are, 92% and 94%. Similar findings were reported by Stonard et al. (2015), Brown & Hegarty (2018), and Peskin et al. (2017). Although these studies present the worrying prevalence of CDA, it should be noted that all the studies that were reviewed were conducted in America. There is very little research discussing the rates and experiences of CDA in young adults within the UK. Though this research is crucial in understanding the impacts and likelihood of CDA amongst young adults, and there may be many similarities in the findings. It should be encouraged that a large body of the existing research cannot be exhaustively generalised to the young adults in the UK as Hobbs et al. (2016) reported that there are many differences in the dating cultures in the UK and USA. Introducing the first hypothesis, 18-20-year- olds with experienced CDA will have experience greater emotional distress than those who have no experience.

Additionally, the ages of American college students differs slightly to the university students in the UK. As some freshers tend to start college at the age of 17, which in the UK is described as adolescent. Studies reporting CDA in adolescences have found far lower prevalence rates, 23% than in university students, 73% (Marganski & Melander, 2015). Thus, the current study is looking at young adults because they have increased access to more advanced technology that offers a permanent connection to the internet, which may explain the difference in prevalence (Borrajo et al., 2015).

Couch et al. (2012) identified online daters are primarily worried about deception, privacy and anonymity risks, emotional vulnerability, and interpersonal intrusiveness (Burke et al., 2011). In spite of the dangers of online dating, a recent study found young adults still prefer online dating and find it safe (Flug, 2016). Research suggests that the level of relationship satisfaction and mental health implications may be moderated by the extent to which the CDA is acceptable to the victim (Schade et al., 2013). Barrajo et al. (2015) reported that most online daters are not aware of what CDA is, or that they are a victim to it, or even perpetrating it as some of the behaviours may not be perceived as abusive. Gámez-Guadix et al. (2018) pointed out some abusive acts are carried out in the context of play or humour that or acceptable signs of concern and love, (Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2020). This could cause numerous acts of CDA to remain hidden behind false justifications (Borrajo et al., 2015). Previously, higher levels of CDA has been associated with the victim experiencing lower levels of relationship satisfaction. However, recent research is highlighting how the perpetration of CDA is becoming less obvious, as there are a number of ways to invade a partner’s privacy or monitor their online activity without them knowing (Borajo et al., 2015). So, victims and perpetrators may present with falsely high levels of relationship satisfaction. Thus, a hypothesis of the current study is victims could present with high levels of relationship satisfaction despite experiencing abusive behaviours and perpetrators may present with lower levels of relationship satisfaction because they are perpetrating for mate retention reasons.

There is little research on the mental health outcomes or levels of relationship satisfactions in perpetrators. There are theories which discuss the onset of perpetration, but nothing on how facilitating CDA affects them. According to the Biopsychosocial perspective, aggressive behaviour is a result of the complex intertwining of the biological, psychological, interpersonal, and environmental components (Defoe et al., 2013).

Introducing the second hypothesis, perpetrators may present with similar mental health outcomes as victims. An increased focus has been placed on the prevalence rates of CDA, the predictive traits of perpetrators, the impact of CDA upon the victim, and their experience of CDA (Borajo et al., 2015). While there is evidence to suggest underlying issues can cause an individual to subconsciously facilitate CDA disguised as mate retention behaviours (Bhogal & Howman, 2018), limited research has been conducted on perpetrator’s experiences and their levels of relationship satisfaction and mental health outcome on a sample of young adults, within the UK. As recommended, more studies should further investigate the impacts of CDA in a British university population (Underwood & Findlay, 2004), inclusive of different ethnicities (Kaura & Lohman, 2007), and genders (Deans & Bhogal, 2017), and to investigate both partner’s experiences and perceptions of the phenomena’s of interest (Sidelinger & Booth-Butterfield, 2007).

Three research questions have been designed. Firstly, what is the role of biopsychosocial factors in the prevalence of perpetrating CDA? Secondly, how does the experience of CDA affect the mental health and relationship satisfaction of those with experience of CDA? Lastly, what are the experiences of 18-20-year-olds who have experienced CDA, in the UK?

Abstract

Background: Infertility is a significant public health issue affecting many women in the reproductive age group; majority of these women are in the developing countries. In Nigeria, it is the most common gynaecological presentation in clinics. Beyond being a medical condition, women with infertility in Nigeria are confronted with socio-cultural challenges. Although, the evidence suggest that female factors contribute only a third to the causes of infertility in a couple, there is the stereotype that women are solely responsible. Consequently, they are disproportionately blamed for childlessness in a union. This has led to psychological and social impacts on these women. This study aims to explore the psychological and social experiences of women with infertility, the contributory and resilient factors.

Methods: Literature search for data was done using electronic databases which included CINAHL Plus, PubMed, Medline, Science Direct and Google Scholar. Relevant search terms were employed and articles retrieved were measured against a set of eligibility criteria. Articles were analysed using the Braun and Clark thematic framework.

Results: The study demonstrated that psychological effects of women with infertility in Nigeria included depression, anger, anxiety, self -guilt and poor self-esteem. The social impacts included marital instability, social stigma and discrimination, domestic violence, suicide, and economic deprivation.

Conclusion: Women with infertility in Nigeria have negative experiences which stem from their socio-cultural environment. Efforts should be geared toward proffering solutions that are holistic in nature at personal, community and governmental levels.

Keywords: Infertility, females, Nigeria, Social, Psychological, Developed countries.

Introduction

Infertility is a global public health issue that continues to be of concern (Kumar and Singh,2015). Clinically, it is defined as the inability to conceive after 12 months of frequent, unprotected sexual intercourse (Elhussein et al.,2019). Two types of infertility exist medically: Primary and Secondary (Vander Borght and Wyns, 2018). Primary infertility is the inability of a person to ever achieve a pregnancy whilst secondary infertility is the inability to conceive following a prior pregnancy. Epidemiologically, it is the inability of a woman in the reproductive age group to conceive for at least two years (Gurunath et al.,2011). The definition of infertility is also determined by the sociocultural context. In some non-westernised settings, it has been defined as not getting pregnant very soon after marriage, having ‘few’ children and not having a male child (Whitehouse and Hollos,2014).

Infertility is named amongst the top six neglected maternal morbidities that occur in developing countries (Hardee, Gay, and Blanc, 2012). Arguably, it has been classified as a disability given its potential to restrict the activities of a woman and limit her participation in every area of life (Khetarpal and Singh,2012). The severity will depend on the socio-cultural environment she finds herself in (Khetarpal and Singh,2012).

Globally, it is said that between 60 and 80 million couples have infertility challenges (Katole and Saoji, 2019). Also, about 186 million women are said to struggle with infertility, with majority of them in developing countries (Dovom et al.,2014). High infertility rates have been reported to occur more in Sub-Sahara Africa; the prevalence is 20%- 46% compared to 10%-15% in developed nations (Panti and Sununu,2014). Consequently, it has been called the ‘infertility belt’, an area which includes West Africa, Central Africa and the eastern regions (Panti and Sununu,2014). This high infertility rates occur together with the high fertility rates in Sub-Saharan Africa, a phenomenon that has been described as “barrenness in the midst of plenty” (Inhorn and Patrizio,2015).

Nigeria is a country in West African with a population of 169 million with 30.8% of couples having infertility concerns (Olarinoye, and Ajiboye, 2019). It is the most common gynaecological presentation in clinics in Nigeria, accounting for 60%-70% of clinical cases (Omoaregba et al.,2011). Secondary infertility is the most prevalent type in women in Nigeria (Adegbola and Akindele, 2013). One of the causes of secondary infertility is infections from unsafe abortion procedures (Emmanuel, Olamijulo, and Ekanem, 2018). A structural problem exists in that abortion services are illegal and the laws restrictive (Emmanuel, Olamijulo, and Ekanem, 2018, p.249). As a result, women resort to visiting unskilled individuals in septic places, who performs procedures that lead to reproductive problems subsequently (Bankole et al.,2015, p.170).

Evidence in Nigeria has shown that the female factors contribute only 30%-40% to the causes of infertility (Odunvbun et al.,2018, p.224). However, women continue to disproportionately shoulder the blame for infertility in a couple (Omoaregba et al.,2011, p.21). With this stereotype that occurs in Nigeria that the infertility problem of a couple stems from the woman, it means that they will carry the psychological and social burdens even though they may not be responsible (Aiyenigba, Weeks and Rahhman,2019, p.77).

Previous researches exist on the psychological and social experiences of women with infertility in several regions of Nigeria (Zuraida,2010; Fehintola et al.,2017; Zubairu and Yohana,2017; Olarinoye and Ajiboye,2019). To the best of my knowledge, the evidence has not been previously compiled and synthesised. A compilation is imperative given the diverse nature of Nigeria with its various ethnic groups. Although, studies have been done on the psycho-social experiences of women with infertility, it is rather small compared to studies done for both male and female experiences. Only women studies are important given that they effects are more negative towards them than men (Deka and Sarma,2015). Evidence show infertility as a challenge yet, more projects are being done for fertility concerns such as the provision of free birth control measures (Hammarberg and Kirkman,2013). A study revealed that mental and behavioural problems are rarely detected during patient consultations at infertility clinics(Makanjuola et al., 2011). It may require that health care providers raise their indices of suspicion. The study will show the effects of infertility on women and enable holistic health care to be delivered. Infertility in women in Nigeria is a social problem and should not be solely ‘medicalised’ as it is been done (Greil et al.,2020).

The aim of the study is to explore and synthesise the psychological and social experiences of women with infertility in Nigeria. The objectives are to determine the psychosocial effects of infertility in women, to examine the contributory effects to these experiences and the resilient factors. The study seeks to answer the following research question: How do the psychological and social experiences differ amongst the women with infertility in Nigeria?

Theoretical Perspective

This study is guided by a theoretical underpinning as developed by Daar and Merali (2002), which provides insights on the psychological and social experiences of women with infertility. Daar and Merali (2002) proposes six levels of the consequences of infertility (Figure 1), with level 1 being the least severe and level 6 the most severe. They argue that the consequences of infertility in Westernised countries are never beyond level 2 while the severity of harm in developing countries are hardly as mild as level 3. This model attempts to bring forward the suffering women with infertility especially in Africa and Asia.

Method

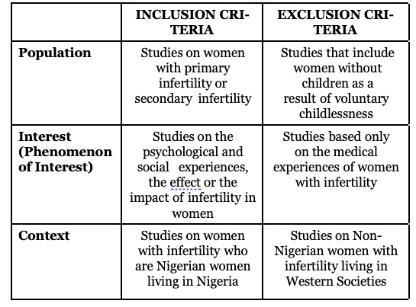

Searches were conducted for primary studies using a range of databases to provide a robust yield. The databases included CINAHL Plus, Pub Med, Medline, Science Direct and Google Scholar. Only articles between 2010 and 2020 were retrieved. Keywords such as ‘psychological experiences’, ‘social experiences’, ‘infertility in women’ and ‘Nigeria’ were used to generate the relevant papers. Synonyms of these keywords were sought and used as well. Keywords were linked together for the search using Boolean operators- (Psychological OR Emotional OR Mental OR Depression) AND (Social) AND (Experiences OR Problems OR Impact OR Effect) AND (Women OR Female) AND (Infertility OR Barrenness OR Childlessness) AND (Nigeria). Also, the search was guided by a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria as seen in the table below. These criteria were made using the Population, Phenomenon of Interest, Context (PICo)strategy.

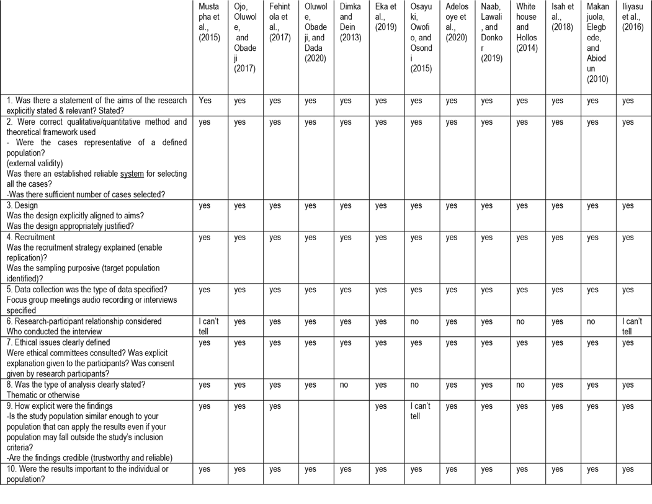

In addition to the electronic data bases search, hand searches were conducted on the reference list of relevant papers. Articles that were written in languages other than English and those that were not peer reviewed were excluded. Quality appraisal was conducted for each of the articles that were included using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist as seen in appendix 1. The checklist includes questions that help to ensure the methodological rigour of each selected article.

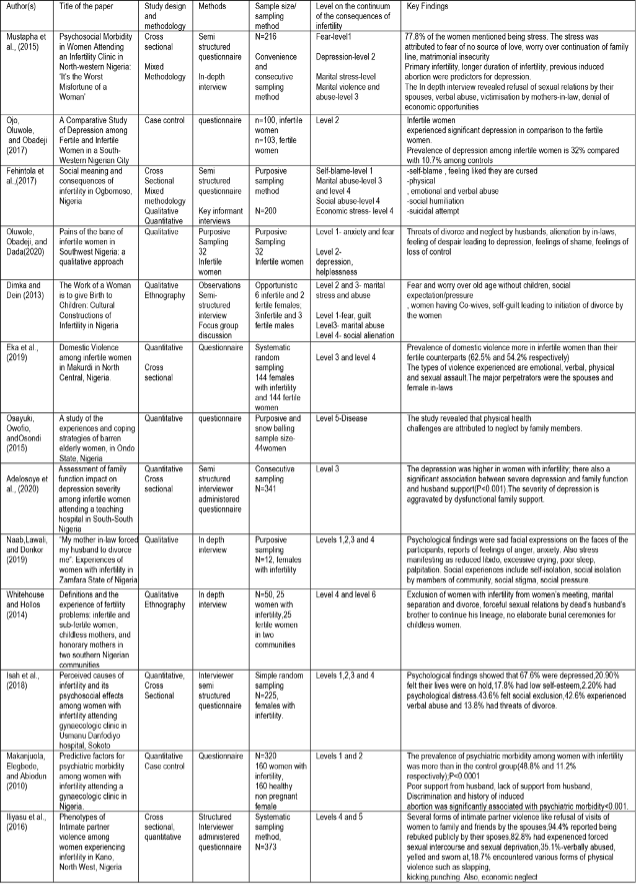

The eligible primary studies were selected and compiled. The data extracted from each study contained the name of the author, year of publication, the title of the paper, study design, sample size and methodology and key findings (Ndarukwa, Chimbari, and Sibanda, 2019). The data analysis method employed was thematic analysis as proposed by Braun and Clark (2006). Recurrent themes from the data were analysed to bring out meanings that will facilitate understanding of the study.

Results

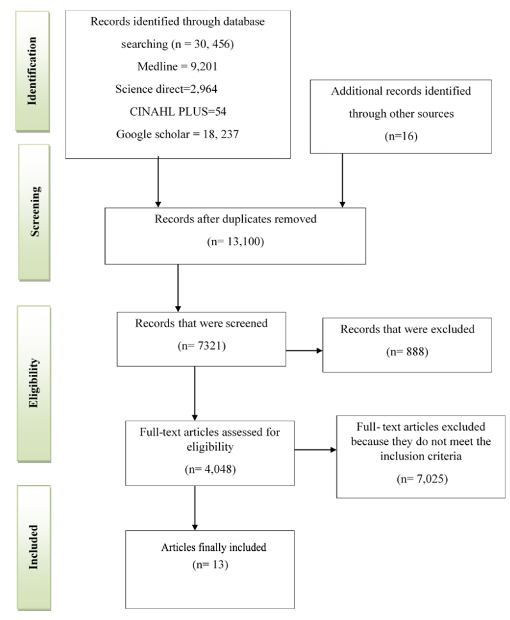

The search result is summarised as shown in the Figure 2. The initial search yielded 30, 456 papers. 13 studies met the eligibility criteria. They include 6 quantitative,5 qualitative and 2 mixed-methods studies. The summary of the 13 included studies are shown in appendix 2.