Dr Dean-David Holyoake, Developmental Editor

“Remember before it happened?” She said, “You know the digi-moment thing.”

I nodded, but couldn’t, “Yeah,” I replied and we both stared ahead.

At ungodly hours I am now able to see relatives a million miles away. I regularly witness colleague’s horrific living room decoration and home furnishing. I marvel at how technology can blur the awful clash of Dralon™ and flowered pattern sofas with electronic party balloon motif and how we apathetically no longer care. I’ve become ritualistic, routinised and every hour check I’ve unplugged the webcam, unmute and hate my new waistline. What does she mean ‘digi-moment’? This may, in the big scheme of things be just a moment, but to suggest it is over or insignificant just wrong. Lockdown has changed more than a moment. Now, I complete my shopping online, give four-star driver reviews and run fingers through fashionable, but longer hair. My new routines, larger waistline and reluctant transformation a result of superhighways, microfibre and silicon so removed from my human condition that I would hardly call it a digi-moment. Lockdown deserves more than just a passing moment, more like a digi-monument I’d say.

“It’s changed the way we all live and learn hasn’t it,” I said.

Lockdown, lockdown and lockdown!

I feel that I have a life which I don’t own

What a dizzy journey walking to the unknown

One minute I am hopeful and next minute I am down

I lost my friends, my resilience and my mojo

I live at home and I work at home as there is nowhere to go

Lockdown! Lockdown! what an embargo!

What a confusion what a vertigo!

Am afraid of the future, am losing "the present"

I have no feeling but like suffering from thirst

Very tricky sphere like surviving in a desert

I lost my confidence if I am completely honest.

But as there is always but there is always another day

That will keep all the muddle at bay

Yes, there is another day

And it will be a safe bay.

Lockdown Experience

Simon Yosef - Doctoral Student, Health

University of Wolverhampton

Although I didn’t realise at the time, beginning a part-time PhD in early February 2020, just weeks before ‘Lockdown 1’, was a little like a scene in an action movie where a character leaps over a rising drawbridge of a castle just in the nick of time. Upon reflection, I feel fortunate to have been able to have experienced an on-campus induction, which has served me well in the initial stages of researching my literature review. Living over 35 miles from campus, I always envisaged making use of online library services and possibly meetings, but little did any of us realise just how much these tools would mean to us in 2020-21.

When applying for a PhD, I anticipated that I would learn new skills and improve established ones. As a mature student for whom IT regularly seems to ‘fight back’ I can confirm that I have now learnt many new things about how IT can assist connectivity with others (Nguyen et al, 2020) and facilitate access to resources, but that from time to time, like a much loved old car, it can and will let you down. I have also learnt that I am not alone in the world of IT ‘fight back’, and therefore to embrace its benefits, and be less worried by its hitches.

Like a wrongly imprisoned person nearing the end of their incarceration, I am longing for a return to a lively campus, to see my supervisory team and attend real events as opposed to online ones. Nevertheless, I can’t help feeling the rush of online, UK wide academic events which emerged during the pandemic have enabled me to meet and make contact (Zheng 2020) with more people than I could ever have imagined in 2020-21 without expensive travel and event fees, and in a timesaving as well as environmentally friendly manner. Beginning to meet and grow into a research network is highly important. Technology made this possible not only for me, but for many others, thus it is only right to celebrate the innovative approaches (Sandars 2020) that evolved as a temporary, pragmatic response to the pandemic, as well as looking forward to all our post pandemic futures.

References:

Nguyen MH ,Hunsaker A and Hargittai E (2020): Older adults’online social engagement and social capital: the moderating role of Internet skills, Information,Communication & Society, DOI: 10.1080/1369118X.2020.1804980

Sandars J, Correia R, Dankbaar M, de Jong P, et al. (2020) ‘Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic’, MedEdPublish, 9, [1], 82, https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1

Zheng F, Khan N A and Hussain S (2020) ‘The COVID 19 pandemic and digital higher education: Exploring the impact of proactive personality on social capital through internet self-efficacy and online interaction quality’ Children and Youth Services Review Vol 119 DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105694

Castles, cars, networks and liberation

Alison Etches - PhD Researcher, Education

University of Wolverhampton

My proposal for researching perceptions of the role of the Biomedical Scientist within patient outcomes involved face-to-face focus groups and interviews with stakeholders of the profession. Biomedical Scientists were, and continue to be, central to diagnostic COVID-19 testing (IBMS, 2020). Due to the impact of COVID-19, revised ethical documentation was submitted for online focus groups and interviews. The Delphi methodology that I used for data collection is known to be more successful if the researcher can develop a rapport with participants as this reduces the likelihood of attrition between rounds of data collection (Keeney, Hassan and McKenna, 2011). The greatest challenge of conducting focus groups and interviews online was how to build rapport with participants to encourage them to engage in subsequent rounds of the study. Utilising online video call technology in data collection has been considered ‘the next best thing’ to face-to-face meetings and participants prefer this to using the telephone (Archibald et al., 2019).

The laboratory response to COVID-19 was significant, with additional staff and resources required to support the service (IBMS, 2020). In response, the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) opened temporary registers for students and former registrants (HCPC, 2020). Laboratory pressures inevitably impacted upon recruitment of participants as I was unable to recruit Biomedical Scientists for a focus group. Instead, I recruited five HCPC registered Biomedical Scientists for online interviews. This was beneficial because the richness of the interview data for the Biomedical Scientist group was combined with the focus group data from the students and academics on the BSc Biomedical Science programme. Integrating focus group and individual interview data can help to enrich conceptualisation of a phenomenon (Lambert and Loiselle, 2008). In addition, attrition rates in the study were relatively low, with 84% of participants completing both rounds of data collection. This is a low attrition rate for a Delphi study with some studies reporting attrition rates greater than 40% (Keeney, Hassan and McKenna, 2011).

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted my data collection methodologies, meaning I had to conduct focus groups online rather than face-to-face. This was challenging as I lacked experience of conducting focus groups and was daunted by the need to build rapport with the participants without meeting them in person. Rapport is developed through establishing common ground, developing a bond and showing empathy (Zakaria and Musta’amal, 2014). Professionally, I had common ground with my participants through my role and empathy for the pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic within their role. The COVID-19 pressures also provided a topic of conversation to begin establishing rapport with the participants. At a challenging time for the Biomedical Scientist profession, online interviews provided convenience and flexibility for the participants as they were arranged at a mutually convenient time without the need to leave their workplace. This is recognised as one of the key advantages of online data collection methods (Archibald et al., 2019). Despite the challenges of researching online, it was important for me to maintain momentum with the study and not pause data collection. Although I had fewer participants than I had intended, the richness and quality of the data I have obtained means that it was beneficial to pursue data collection using online technologies.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenging time to be a doctoral student and has provided a test of resilience and determination to succeed. However, it has provided opportunities to study with fewer distractions and to utilise technology to conduct research remotely.

References:

Archibald, M.M., Ambagtsheer, R.C., Casey, M.G., Lawless, M., (2019). Using Zoom Videoconferencing for Qualitative Data Collection: Perceptions and Experiences of Researchers and Participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 18, pp 1-8.

Health and Care Professions Council (2020). COVID-19 Temporary Register. Available at: COVID-19 Temporary Register | (hcpc-uk.org) (Accessed 21/02/21)

Institute of Biomedical Science. COVID-19 recommendations for laboratory work. Available at: COVID-19 - recommendations for laboratory work - Institute of Biomedical Science (ibms.org) (Accessed 21/02/21)

Keeney, S., Hasson, F., McKenna, H., (2011). The Delphi Technique in Nursing and Health Research. Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Lambert, S.D., and Loiselle, C.G., (2008). Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 62 (2), pp. 228-237

Zakaria, R., and Musta’amal, A.H., (2014). Rapport building in qualitative research. EPrints Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. Available at: http://eprints.utm.my/id/eprint/61304/1/AedeHatibMustaamal2014_RapportBuildinginQualitativeResearch.pdf (Accessed 24/02/21)

Researching through a computer screen: the impact of COVID-19

Kathryn Dudley - BSc(Hons), MSc, CSci, PGCert, FHEA, MIBMS - Doctoral Student, Health,

University of Wolverhampton

Covid-19 has had substantial suffocating impacts on our lives in diverse ways, be it our day to day lives, jobs, studies, exercise, local recreational activities, travelling abroad, festivities. Strictly time-bound life patterns transformed into less disciplined virtually operated living. To briefly shed light on these elements, I feel the urge to call for a new definition of Living and Learning in line with the altered constituents of our lives. Turning attention to the living aspect, my experienced, teaching professional self, transformed into a foreigner in the field of teaching where the use of conventional teaching methods became unsought. Thus, it became incumbent upon us, as teaching professionals, to utilize fashionable avenues of teaching digitally, and for this acquiring training on fresh or existing technological tools became mandatory. Exploring new virtual methods of teaching and the nonstop professional development through the extensive use of digital tools not positively impacted on health and domestic life.

On the flip side, the lockdown regulations made teaching on-site defunct which provided me with the potential possibility of maximizing my personal commitments and occupying myself in writing literature for my thesis. Naturally, the absence of provision of visiting libraries and the chance to study in a scholarly environment barely reinvigorated. Similarly, restrictions on social interaction with the community of practice froze and disrupted the discourse that has challenged my philosophical underpinning. Embedding the virtual culture for professional demands became a nuisance to an extent that I could not allow myself to engage electronically for my research purposes. However, connections through MS Teams and Zoom have appeared to be effective that gave me an allowance to attend across the borders, Annual Progress Review, conferences and university seminars.

It seems to be guaranteed that even after the departure of COVID-19 from our lives, life will experience a new normal phenomenon. Perhaps a new era, a small revolution in its own way.

Living, Learning and Lockdown

Ambreen Alam - Doctoral Student, Education

University of Wolverhampton

Lockdown 3.0 in the UK has coincided with my attempts to write a methodology chapter. This has meant grappling with the complexities of paradigms, ontology and epistemology whilst sharing responsibility for home schooling my daughter. Even when I’m off teaching duty the interruptions are seemingly constant. “Dad, do you want to play?”. “Dad, can I have a snack?”. “Dad…actually you’re not very good at maths, I’ll ask mummy”. The luxury of having long periods of time to read, write and reflect is a distant memory.

Evaluating the potential incommensurability of post-positivism and constructionism whilst negotiating the hurdles of the primary school curriculum is no easy task, especially when my desk has been invaded by My Little Ponies. I suspect their appreciation of the literature is better than my own. I’m sure Denzin and Lincoln didn’t have to put up with this. What I have learnt, with a level of certainty not traditionally associated with qualitative research, is that studying for a PhD and teaching a 5-year-old are fundamentally incommensurable.

I feel sure that my frustrations will resonate with parents everywhere who are trying to balance the demands of home working, home schooling and answering the door to the delivery driver. And yet, whilst progress has been dishearteningly slow at times, it has also been a joy to spend so much time with my family. There are other upsides too. Whilst my understanding of interpretivism is probably not what it should be, my phonics have really come on and if you ever want to know about the life cycle of a turtle, I’m your man.

Reflections on the incommensurability of social constructionism and My Little Ponies

Mark Elliot - PhD Researcher, Education

University of Wolverhampton

Covid 19 pandemic has influenced health and wellbeing research activities globally with many abruptly shutting down for safety reasons (Ataullahjan et al, 2020; Kozlowski et al, 2020). In- person participation, where essential studies were still running, was negatively affected (Cardel et al, 2020, Padala et al, 2020). I had to surmount the challenges posed by covid 19 pandemic by redesigning my doctoral research. Although the millennial generation (MG), my research subjects, are reputed to be digital natives and thus comfortable with the use of technology (Dahl et al, 2018; 2018; Fletcher and Mullett; McGloin et al, 2016), I had not contemplated the use of technology in the initial design of my data collection method. I wanted to collect “story artefacts” in form of hard copy collages so as to reflex on them and make ethnographic sense out of them (Cross and Holyoake, 2017). But face to face contacts became apparently impossible due to covid 19 lockdown.

Through reflection, it occurred to me that I could collect the same data digitally using Skype. I thus modified my initial research proposal and applied for and was granted ethical approval based on the reviewed data collection method. Collecting data digitally helped to save the time and the money required for the participants to come down to the initially proposed data collection centre. This thus reduced respondents burden, a key reason for non-participation in health studies (Callinan, 2017; Scuderi et al, 2016; Ziegenfuss, 2010).

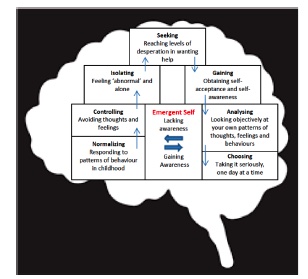

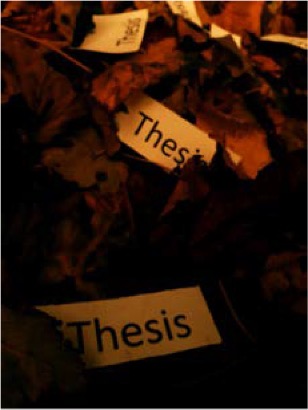

This image which was digitally collected as a "story artefact" was provided by a participant as their representation of what apparent self-care looks like to them. I am currently working to construct metaphorical meanings from it. Suffice to stay that it demonstrates unequivocally that the data I wanted to initially collect in hard copies via face to face approach could be collected digitally as well. The MG are very busy with study or work and sometimes come across as hard-to-reach (Alsop, 2008; Baiyun et al, 2018; Winter and Jackson, 2016; Woodard et al, 2000). My experience with collecting data digitally made me to think that the problem reaching the MG may have to do more with the data collection methods utilised than their assumed unwillingness to participate in research. I recommend that even if life returns to normal from the covid 19 challenge, the digital technology should still be utilised as much as possible in health and wellbeing studies involving the MG (Cowey and Potts, 2016; Ransdell et al, 2011)

Fig 1: A non-personal collage digitally collected from one of my research participants.

References:

Alsop (2008) The Trophy Kids Grow Up: How the Millennial Generation is Shaking Up the Workplace. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Ataullahjan, A., Kortenaar, J., & Qamar, H. (2020).Towards more equitable global health research in a COVID‐19 world. Social Anthropology, 28(2), 224-225.

Baiyun G., Ramkissoon, A., Greenwood, R.A. Hoyte, D.S. (2018) ‘The Generation for Change: Millennials, Their Career Orientation, and Role Innovation’, Journal of Managerial Issues, vol.30, no.1, pp.82–96.

Callinan, Sarah. (2017). The Impact of Respondent Burden on Current Drinker Rates. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(11), 1522-1525.

Cardel, M. I., Manasse, S., Krukowski, R. A., Ross, K., Shakour, R., Miller, Lemas, D.J., and Hong, Y. (2020). COVID‐19 Impacts Mental Health Outcomes and Ability/Desire to Participate in Research Among Current Research Participants. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 28(12), 2272-2281.

Cowey, A.E. & Potts, H. W.W. (2018) "What can we learn from second generation digital natives? A qualitative study of undergraduates’ views of digital health at one London university", Digital Health, vol. 4.

Cross, V. and Holyoake, D.-D. (2017) ‘“Don”t just travel’: Thinking poetically on the way to professional knowledge’, Journal of Research in Nursing, 22(6–7), pp. 535–545. doi: 10.1177/1744987117727329.

Dahl, A. J., D’Alessandro, A. M., Peltier, J. W., & Swan, E. L. (2018). Differential effects of omni-channel touchpoints and digital behaviors on digital natives’ social cause engagement. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 12(3), 258-273.

Fletcher, S. and Mullett, J. (2016) “Digital Stories as a Tool for Health Promotion and Youth Engagement.” Canadian Journal of Public Health, vol. 107, no. 2, pp. e183–e187.

Kozlowski, H.N., Farkouh, M.E., Irwin, M.S., Radvanyi, L.G., Schimmer, A.D., Tabori, U. & Rosenblum, N.D.( 2020) "COVID ‐19: a pandemic experience that illuminates potential reforms to health research", EMBO Molecular Medicine, vol. 12, no. 11.

McGloin, R., Richards, K. & Embacher, K. (2016). Examining the Potential Gender Gap in Online Health Information-Seeking Behaviors Among Digital Natives. Communication research reports, 33(4), pp.370–375.

Padala, P. R., Jendro, A. M., Gauss, C. H., Orr, L. C., Dean, K. T., Wilson, K. B., Parkes, C.M. and Padala,

K. P. (2020). Participant and Caregiver Perspectives on Clinical Research During Covid‐19 Pandemic. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 68(6), E14-E18.

Ransdell, S., Kent, B., Gaillard‐Kenney, S. & Long, J. (2011). Digital immigrants fare better than digital natives due to social reliance. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(6), 931-938.

Scuderi, G.R., Sikorskii, A., Bourne, R. B., Lonner, J.H., Benjamin, J.B. and Noble, P. C. (2016). The Knee Society Short Form Reduces Respondent Burden in the Assessment of Patient-reported Outcomes. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 474(1), 134-142.

Winter, R. P. and Jackson, B. A. (2016) Work values preferences of Generation Y: performance relationship insights in the Australian Public Service. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 27(17), 1997-2015. 19p.1 Diagram,3 Charts. Database: Education Research Complete.

Woodard, D.B., Jr. Love, P., and Komives, S.R. (2000) Students of the new millennium. In Leadership and Management Issues for a New Century. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 92: 35-47

Ziegenfuss, J.Y. (2010) "Embedded authorization form also reduces respondent burden", Journal of clinical epidemiology, vol. 63, no. 6, pp. 591-593.

Millennial Generation Apparent Self Care

How Covid 19 Lockdown Changed my Data

Enemona Jacob, Dean-David Holyoake, Hilary Paniagua - Doctoral Student, Education

University of Wolverhampton

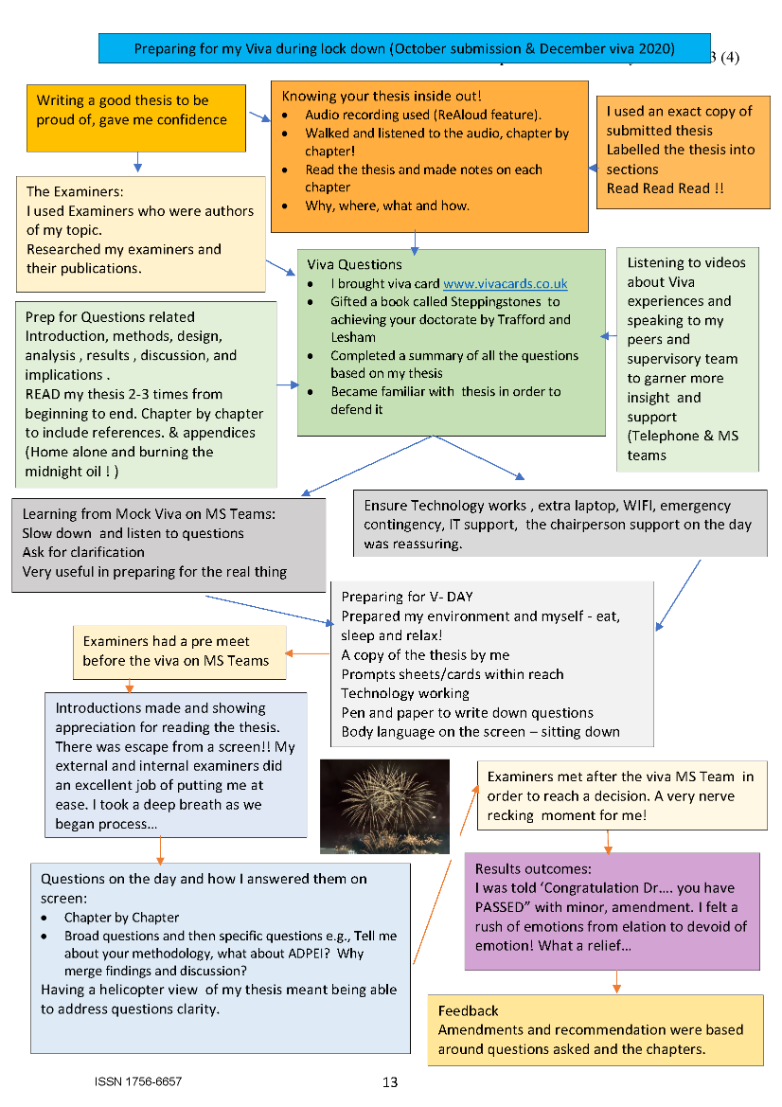

Writing a good thesis during a pandemic was not easy, I’d say. I was faced with enormous challenges of confinement related to a lack of freedom and social isolation. Working from home provided plenty of welcome distractions away from my study. I stayed focus and motivated as I threw myself into learning my thesis, chapter by chapter. For me, even in isolation, I remained connected to the combined support of my family, peers and supervisory team. The mock viva awakened my fears and may be eager to read and read!! Intertwined in my learning was messages: Stay alert, control the virus, stay safe or stay home, protect the NHS, save lives; a reminder that we exist in very serious times.

I confronted the challenge of a good work-life balance very badly, gained pounds on the scales and had an inferior sleeping pattern as I worked early morning or very late nights. The virtual world and all its technology were a steep learning curve; having a contingency to avoid a disaster was essential. When V-Day arrived virtually on MS Teams, I rose above the emotional roller coaster and hovered in anticipation. The environment was prepared; the laptop charged, spare glasses, my thesis, prompts and cards and oh yes! a drink of water were all carefully arranged! The screen was ready, technology checked and working, the chair and supervisor was there on hand for support and ran through the process before I began my viva. Finally, I was in the moment, no pressure! I was on screen, and there were my three examiners.

Let the performance begin!! The examiners wrapped me in compassion, the very topic of my thesis. I felt tranquilised and very much at ease. Questions were broad and narrow, deeper and deeper, we went. The time went quickly and then went slowly, as I waited for my decision. I didn’t and couldn’t eat, spoke to family and peers. As I joined MS teams, in those precious moments, I felt alone, although, at that moment, there were faces over all the screen. Congratulations, Dr Juliet Drummond, you have passed with minor amendments. The news brought me close to surrealism; as I received some verbal feedback, I tried to make notes of the amendments. All in all, it was a wonderful opportunity and a unique experience, full of meaningful exchanges of knowledge, to be treasured for many years to come. Merci to all my participants, supervisory team, lecturers, managers, star office, peers, friends and family; you have contributed to making my doctoral journey a positive one.

Viva Le Lockdown

Juliet Drummond - Professional Doctoral, Health

University of Wolverhampton

The pandemic that has restricted the movements and froze lives globally was treated diversely in my region, United Arab Emirates. The authorities invested in embedding E-learning's culture and assigned a budget for sanitizing streets, public places and laid easy to access Covid testing services throughout. Formerly, having moderate expectations to teach through the smart technological tool suddenly became mandatory. In addition to that, the non-stop arrivals of branded teaching tools to facilitate remote teaching took my career to the infancy stage. However, the learners' increasing interest made me realize that perhaps now was the time for teaching and learning to be evolved at this revolutionary rate. It seems unlikely to imagine that teaching institutes will revisit those former territories and pedagogies that are overtaken by the digitalized world. Nevertheless, the burgeoning popularity of electronic teaching platforms and the network may anticipate scrutiny in terms of cybersecurity and health-oriented concerns.

Shedding light as a researcher, the lockdown has denied me the opportunities to hold meaningful debates with other professionals who has been providing me with new dimensions philosophically and forced me to explore and ponder my area of research. Reading, writing, preparing lessons and activities for my online lessons, became around the clock job. Ultimately, the designated time to skim through peer-reviewed articles and online research books became a secondary preference. The continuous writing spirit and the art of critiquing became rusty and I found myself in the phase when I have begun my doctoral degree and learnt to adopt academic writing tactics. The enthusiasm and motivation to complete my doctoral journey became an illusion. The positive aspect of this pandemic, however, is the online provision of the doctoral college’s workshops, sessions and conferences. Keeping up with social interaction boundaries, I intend to avoid haste in commencing fieldwork and therefore planning to tweak my doctoral development plan.

Living, Learning and Lockdown

Muhammad Zubair - Doctoral Student, Education

University of Wolverhampton

My research involved interviewing self-confessed perpetrators of domestic abuse. The interviews looked at understanding why such men, voluntarily attended psychologically informed intervention programmes for the desistance of domestic abuse. I hold a somewhat overly optimistic view that it is possible to end domestic abuse. I am not too sure whether that is something that would happen in my lifetime, but I am hopeful that someday domestic abuse will be a thing of the past. In the most simplistic sense, I believe most people need guidance on how to be in a relationship.

I was intrigued whilst talking to the men and felt a sense of understanding of their experiences. However, this changed when news articles and media reports highlighted a significant increase in domestic abuse related deaths during lockdown. This left an intense feeling of shock and discomfort inside of me. During my research I needed to be empathetic and accepting towards the experiences of the men. Many of the men had lost contact with a child due to their abusive behaviours. It was hard not to be saddened by their emotive accounts of how they missed their children and desired nothing but to be able to see them again. But now I was reminded of the ugliness of domestic abuse and the very real extremes of what domestic abuse can lead to. Being in lockdown, having no escape, having no access to support systems and the fear of what could happen if the wrong thing was said or done. A very bleak image occupied my mind whilst I went over the interviews, transcribed and analysed my research.

It might seem naive, that I was so surprised by the reality of domestic abuse resulting in death. But I also recognise, at times we create a ‘box’ in which we contain certain information, in order for us to be able to cope with the difficult information which lies ahead. This is what I did while I spoke to the men. How else would I been able to understand a man who had hit, stalked and controlled a woman but also was so very desperately trying to better himself for his child?

The Ugliness of Domestic Abuse During Lockdown

Tarnveer Kaur Bhogal - Counselling Psychology Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

Earlier last year, the whole world came to a standstill. In March 2020, the United Kingdom (UK) experienced a nationwide lockdown, and society could not go into work, travel or meet individuals face to face. This was due to a deadly virus called "corona, also known as COVID-19". A message from the UK's Prime Minister Boris Johnson was broadcast daily on national television advising individuals to "stay at home, protect the NHS and save lives". This catchy slogan became embedded in the national consciousness in the pandemic's early days (McGuinness, 2020). The initial approach to communication about the virus was complacent (Sanders, 2020). This rapidly started to feel like a tape recorder set on replay as the words echoed around my household, and my family panicked with anxiety.

Before the pandemic, I had never heard of the online video chat tools called Zoom or Microsoft Teams. These immediately became popular and the 'new norm' that everyone knew and talked about (Marks, 2020). This video chat platform swiftly became the highlight of my day as I was itching to communicate with work colleagues and lecturers to have virtual face-to-face contact with the outside world and structure my working day. Our communication method readily became so different, and I would feel nervous about seeing work colleagues behind a laptop screen; it was awkward to begin with.

As months passed by, the UK's covid-19 death toll had gradually risen, and I began to experience a turmoil of emotions. I felt that things would not change anytime soon, causing me to feel hopeless about my future doctoral career. During this worrying time, I also continued working at HMP Whitemoor to support prisoners in managing their mental health difficulties. Some days felt massively anxiety-provoking, but I could bracket my feelings of worry by utilising grounding techniques and validating my irrational thoughts (Spinelli, 2005; Benedicto, 2018; Hazlett-Stevens, 2018; Hoffman & Gomez, 2017).

A few weeks later, I began to find ways to self-motivate and reflect on my doctoral research thesis. I recalled research on the back burner as clinical duties and responsibilities were a greater priority within the National Health Service (NHS). I was keen to proceed with my research topic and felt passionate about completing what I had already started. I began to think creatively about making subtle changes to my research project and conducting data collection during unprecedented times, bearing in mind that the main priority was to keep safe and socially distant. As I brainstormed a few ideas around using video chatting tools to interview fellow research participants, I started to feel a sense of positivity entering into my body. I recognised that I had a plan B, and it left me feeling exhilarated.

It was surreal, and I felt excited to virtually conduct research data collection and keen to add a new experience to my doctoral research journey. There was a space of inner enthusiasm and passion about my future which blossomed inside me, allowing me to adapt to a positive mindset. I kept reminding myself "to take one day at a time," these words supported me to manage my worry (Vivyan, 2018; Wells, 1995). In effect, I became my self-therapist, where I had used tools and resources to cope with a pandemic. I felt there was an opportunity to offer self-compassion and practise what I preached as a counselling psychologist in training (Gilbert, 2009).

I am currently in the process of editing my research proposal, ensuring that practicalities have been considered to conduct research data collection in line with the UK's current government social distancing guidelines, alongside adhering to local NHS research and university policies. I hope to safely continue with my doctoral research journey during a time of uncertainty by utilising creativity and adapting to the unexpected. I have learnt a lot about myself in the year 2020, something that I will cherish for the rest of my life. I have learnt about my inner strengths, ability to persevere and draw upon my resilience. I have practised gratitude and focused on what I need to appreciate in life to strive each day.

I have an image in mind that I would like to share and that "there will be light at the end of the tunnel".

References

Benedicto, E. (2018). Mindfulness-based intervention in patients with generalised anxiety disorder, Relias Media, Retrieved from: https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/142761-mindfulness-based-intervention-in-patients-with-generalized-anxiety-disorder

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric treatment, 15, 199-208.

Hazlett-Stevens, H. (2018). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for generalised disorder: does pre-treatment symptom severity relate to clinical outcomes? Journal of Depression and Anxiety Forecast, 1(1), 1-4. Retrieved from: https://scienceforecastoa.com/Articles/JDAF-V1-E1-1007.pdf

Hoffman. S.G. & Gomez, A.F. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(4), 739-749.

Marks, P. (2020). Virtual collaboration in the age of the Coronavirus. Communications of the ACM, 63(9), 21-23. DOI: 10.1145/3409803.

McGuinness, A. (2020). Coronavirus: How the PM’s slogans have changed. Sky News, retrieved from: https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-how-the-pms-slogans-have-changed-12040037

Sanders, K. B (2020). British government communication during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic: learning from high reliability organisations. Church, Communication and Culture, 5(3), 356-377.

Spinelli, E. (2005). The Interpreted World: An Introduction to Phenomenological Psychology (2nd edition). London: Sage.

Vivyan, C. (2018). Vicious Cycle of GAD and Worry. Get Self Help website, Retrieved from: https://www.getselfhelp.co.uk/gad.htm

Wells, A (1995). Meta-cognition and worry: A cognitive model of generalised anxiety disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 23: 301-20.

“I think we all understandably get caught up at times in wanting

certainty and yet I believe that it can indeed contribute…

to a state of paralysis and lack of creativity”

(Mason, 1993, p. 190).

For my research, my interviews investigating the experiences of online negative comments for adults with learning disabilities were to be face-to-face. Prior to the pandemic, my research interviews had only ever been face-to-face or via the telephone, never using online video platforms. I was aware of my anxiety around online interviewing due to the unknown. However, rather than gripping solely to my certainty and staying in a state of paralysis, I delved into a position of ‘safe uncertainty,’ encompassing a way of being which prioritises both curiosity and difference (Mason, 1993). Through this, I became curious around the different online video platforms, taking the time to learn and become familiar with them, for example learning how to utilise the screen share function to share my images so I could creatively meet the unique needs of the individual with intellectual disabilities (Prosser & Bromley, 2012).

Yet, further challenges that have emerged, where due to staring at a computer screen all day, I am beginning to experience ‘Zoom Fatigue’ (Fosslien & Duffy, 2020). In overcoming this challenge, I have prioritised self-care, an area historically neglected by myself, psychologists and those in the ‘helping’ professions (Rothschild & Rand, 2006). For me, this has taken the form of regular breaks away from my computer screen, walks outside in nature (Figure 1), which has been beneficial in giving me more energy to stay on focus. If COVID-19 has helped me learn anything as a researcher, it is the importance of a compassionate approach to self, others and research (Gilbert, 2010).

References

Fosslien, L., & Duffy, M. W. (2020). How to combat zoom fatigue. Harvard Business Review, 29.

Gilbert, P. (2010). The compassionate mind: A new approach to life’s challenges. London: Constable.

Mason, B. (1993). Towards positions of safe uncertainty. Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation &: Management, 4, 189–200.

Prosser, H., & Bromley, J. (2012). Interviewing People with Intellectual Disabilities. In E. Emerson, C. Hatton, K. Dickson, R. Gone, A. Caine, & J. Bromley (Eds.), Clinical Psychology and People with Intellectual Disabilities (pp. 105–120). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118404898.ch6

Rothschild, B., & Rand, M. L. (2006). Help for the helper: The psychophysiology of compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma (1st ed). New York: W.W. Norton.

Living, Learning and Lockdown

Fiona Clements, MA MSc - Counselling Psychology Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

The transmission of Covid-19 has been rapid through the global populace, invoking fear, illness and death upon millions. Our day to day journeying bought to a rather abrupt hiatus! With little time to process the speed of such drastic incarceration, with the loss to routines, pace and ways of living, time seemed to stand still encased in ‘bubbles’ of modified yet ‘enforced reality’. Rather like the respiratory virus, there was a feeling the world had paused for breath, whilst tragedy unfolded. For many, this existence undoubtedly involved significant periods of loneliness and isolation (Hwang et al., 2020), which may have greatly impacted on mental health (Pietrabisa and Simpson, 2020; Killgore et al., 2020). Conversely, others may have seized the moment to breathe life into new virtual ventures (Maritz et al., 2020). However, as I reflect from experience, it is the deafening sense of loss that is prominent; this ‘loss continuum’ being felt on a multitude of different levels with varying degrees of intensity and emotion.

Indeed, the experience of loss is undoubtedly subjective, but what was prominent during lockdown were the taken for granted day to day rituals. For example, the school run, journey to work, and those benign corridor conversations with colleagues. Not to mention, the friendly handshake, hug and numerous other tactile gestures that are so integral to being human. Then, there is the loss of a loved one and the grief that ensues and Covid-19 has inflicted this in abundance, with the potential for prolonged impact on the health and wellbeing of those left grieving (Pearce, Honey and Lovick, 2021). Bereavement may bear a profound sense of emptiness, giving rise to a cocktail of feelings such as anger, frustration, guilt and sadness, not to mention a void that threatens to engulf the path. Thus, whatever form loss takes, it may run deep, cutting to the core of existential experience with a sense of ‘nothingness’; from which may come healing (Christ, 1995). As I pause and ruminate these emotions swirl, there are ripples of new insight unfolding, the silence lifts; and life appears to become more audible. A circularity of being that at times has been crippling brings clarity of mind, “a reality of metanoia” (Wright, 2005 p.193), bearing forth a renewed sense of hope. It is at the point of this new position that there is an unfolding awareness that the silence may have served to enable a new vision, whilst learning to have greater empathy for self and others.

References

Christ, C. (1995) Diving Deep & Surfacing: Women Writers on Spiritual Quest. Boston: Beacon Press.

Hwang, T., Rabheru, K, Peisah, C, Reichman, W., & Ikelda, M. (2020) Loneliness and social isolation during the COVD-19 pandemic. International Psychogeriatrics, 32 (10), 1217-1220.

Killgore, W., Cloonan, S.A., Taylor, E.C & Dailey, N.S. (2020). Loneliness. A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research, 290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020. 113117.

Maritz, A., Perenyi, A., de Waal, G., Buck, C. (2020) Entrepreneurship as the Unsung Hero during the

Current COVID-19 Economic Crisis: Australian Perspectives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4612.

Pearce, C., Honey, J.R., Lovick, R. (2021) ‘A silent epidemic of grief’: a survey of bereavement care provision in the UK and Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e046872.doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046872.

Pietrabissa, G and Simpson, S.G. (2020) Psychological Consequences of Social Isolation During Covid-19 Outbreak. Front. Psychol. 11:2201. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02201

Wright, S. (2005) Reflections on Spirituality and Healthcare. Whurr Publishing.

EDITORIAL

Dr Hilary Paniagua

Editor-in-Chief

The 21st century has proved to be a challenging period however it can still be a dynamic and exciting time for research particularly where it is creative. For many years science disciplines have allied themselves only to a conception of knowledge that advocates procedural approaches and values associated with hard facts and replicability. Such thinking also presumes there is a fixed nature of subject matter that is independent of anyone’s particular prejudices and advocates propositions that are only supported and reinforced by empirical evidence. This traditional research thinking can no doubt be creatively devised but at the same time in its practice its aim can be to avoid creativity. In contrast there is now a transformative movement within research that embraces subjectivity and a belief that research can also be valued creatively through the lens of artistic practice. Such creative thinking about research is particularly useful at the start of a project, when all things are possible however it can also be used at every significant stage of the research process as well as in everyday research activities. This edition illustrates exactly this creative endeavour from its front cover through to its content of poems, limericks, pictures and posters, all of which have been created by Wolverhampton University’s research students and staff. If you have any reservations as to what is before you in this edition maybe I can leave you with the views of a JHSCI colleague?

“I have never worked in research, but I realise now how much work is

involved and how students move through their doctoral journey. I think

these are really nice reflections. It has been wonderful to take some time

out of a busy day to just sit and read these”

My portfolio unfolds through a series of letters. But why letters, you ask? Well, it is difficult to envisage a return to those days when handwriting and hand-written letters seemed so pivotal in the exchange of messages especially between people separated by time and place. I remember those days well when letters written by me on blue paper marked ‘air mail’ reached their destination at least a week after posting. I imagined my sister running to the front door at the sound of the postman’s cycle bell. She would then sit in the kitchen and read out my letter to the whole family, giving them news about my days in England. I imagined my mother listening intently whilst chopping vegetables and interrupting with questions about my plans to visit home. I imagined everyone wanting to take their turn at handling the letter afterwards.

Every day I would check my letter box for a reply, certain in the knowledge that very soon there will be an airmail addressed to me complete with the scent of home, the scent of Mauritius. The 1970s have now faded into a distant past, and hand- written letters sent and received lie in the darkness of a treasure chest, a time capsule.

Letter-writing, referred to as ‘epistolary intent’, is an intention to communicate by letter with someone who ‘is not there’, motivated by the expectation of a response (Stanley, 2015). The letter, some would argue (Milne, 2010), also communicates many aspects of the letter writer’s personal characteristics. The recipient can sense traces of the writer such as their touch on the paper and their licking of the stamp. Similar intangible effects such as the aura or living hand of the writer is believed to radiate from their writing (Phillips, 2010). The more tangible attributes relate to the material aspects of the letter, that it can be read and re-read, passed on to others, destroyed or saved and kept. It can also be bought or sold or sought out by researchers or by those interested in its historical significance.

Despite these noteworthy characteristics, the letter is unlikely to continue to exist as a serious form of everyday communication. Epistolary seems destined to be fulfilled by other means. Everything is or will be typed or texted or twittered or emailed or attached to an email. Emotions will be expressed by means of emoticons and personalised signoffs. But despite its heralded demise, letter- writing has been used as a form of narrative therapy in counselling psychology (Mosher and Danoff-Burg, 2006; and Hoffman, 2008) and more recently Pithouse-Morgan et al., (2012) used letter-writing as a collaborative auto-ethnographic research method. They argued that letter-writing used in qualitative research generates self- reflexive data, the analysis of which enables participants to re-examine their own identities as well as their lived experiences.

Whilst I am drawn to the notion of letter writing as a reflexive auto-ethnographic research method, I am even more seduced by the nostalgia of those less tangible effects of letters particularly those written with affection: the thrill of receiving such a letter delivered by post, my name lighting up the envelope; the palpable sense of urgency and anticipation that it creates in me; the need to find a quiet corner removed from the rest of the world where I can open the letter in such a way that it speaks to no-one but me; the first words, Dear or My Dear, or My Darling, words that give me a deep sense of pleasure and make me believe that I exist or that I matter; sentences that carry me instantly to the letter writer or to places in my imagination; the freedom to choose to share its contents; and the desire to treasure it and keep it somewhere safe along with other precious letters.

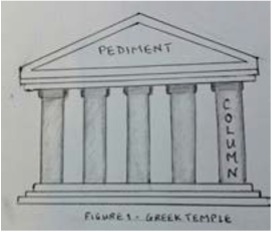

Because of these not so scholarly reasons, I signpost my portfolio by means of letters I have written, letters I am writing and letters I should have written. The letters provide what Maxwell and Kupczyk-Romanczuk (2009, p.140) identify as the linking theme, the ‘over-arching pediment (roof)’ of the Greek temple holding together a row of columns, each symbolising a separate piece of work (please see Figure 1 below).

The columns and the pediment represent a coherent and connecting model for the portfolio, although I concede that reality is not necessarily orderly, coherent and simple. Instead it can be fragmented and chaotic with discontinuities (Heylighen, 2018), even more so in a Post-Covid- 19 world, a world in which a hand-written letter has the capacity to disrupt and deliver something unintended and sinister. On account of this, you the reader may refuse to accept anything sent on paper, at least until the danger of Covid-19 has passed and confidence in the magic of letters is restored.

Composed not with pen and paper but with sincerity, my first letter grows restless at the starting block. So, if you are sitting comfortably, allow me to begin.

My Dear …

References

Heylighen, F. (2018) Post-Modern Fragmentation [online]. [Accessed 13 August, 2018]. Available at: http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/POMOFRAG.html

Hoffman, R. M. (2008) Letter Writing: A Tool for Counsellor Educators. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health 3(4) pp. 345 – 356.

Maxwell, T.W. and Kupzcyk and Romanczuk, G. (2009) Producing the professional doctorate: the portfolio as a legitimate alternative to the dissertation. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 46 (2) pp. 135 – 145.

Milne (2010), In: Stanley, L. (2015) The Death of the Letter? Epistolary Intent, Letterness and the Many Ends of Letter-Writing. Cultural Sociology 9 (2) pp. 240 – 250.

Mosher, C. E. and Danoff-Burg, S. (2006) Health Effects of Expressive Letter Writing. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 25 (10) pp. 1122 –1139

Phillips, S. (2010) Should you feel sad about the demise of the handwritten letter? [online]. [Accessed August 13, 2018]. Available at: https://aeon.co/ideas/should-you-feel-sad-about-the-demise-of-the-handwritten-letter

Pithouse-Morgan, K., Khau, M., Masinga, L. and Van De Ruit, L. 92002) Letter to Those Who Dare Feel: Using Reflective Letter – Writing to Explore the Emotionality of Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 11 (1) pp. 40 - 56

Stanley, L. (2015) The Death of the Letter? Epistolary Intent, Letterness and the Many Ends of Letter-Writing. Cultural Sociology 9 (2) pp. 240 –

Portfolio Through Letters

Yash Gunga Professional Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

As a trainee Counselling psychologist, I identify with the discipline’s endeavour to address oppression and promote social justice. My research on the experience of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in South Asian Women moved me to such direction. Interviewing these women highlighted to me the many forms of oppression that one may experience in our society. Immersing myself in the interviews with my participants, I noticed myself asking: what does it feel to live with IBD? What does it feel to live with IBD as a woman within a culture, where women’s value is highly determined by the level and nature of care she can provide as a mother, a daughter, a daughter-in-law and a spouse?

Delving deeper into my research data, I felt increasingly drawn into exploring the different levels of power associated with sociocultural characteristics that we all inherit from our context. I wondered about how the women thought and talked about IBD and how this influenced their views about themselves and perceptions of others. This led me to Michel Foucault (1926-1984) and his argument that power is based on knowledge that in turn reproduces. I then asked some more questions: what power is held within the women’s sociocultural discourses about femininity and womanhood, what knowledge do these discourses reproduce and with what effects? These are the questions that I am hoping to answer with my research and as a Counselling Psychologist contribute to a movement that challenges oppressive discourses.

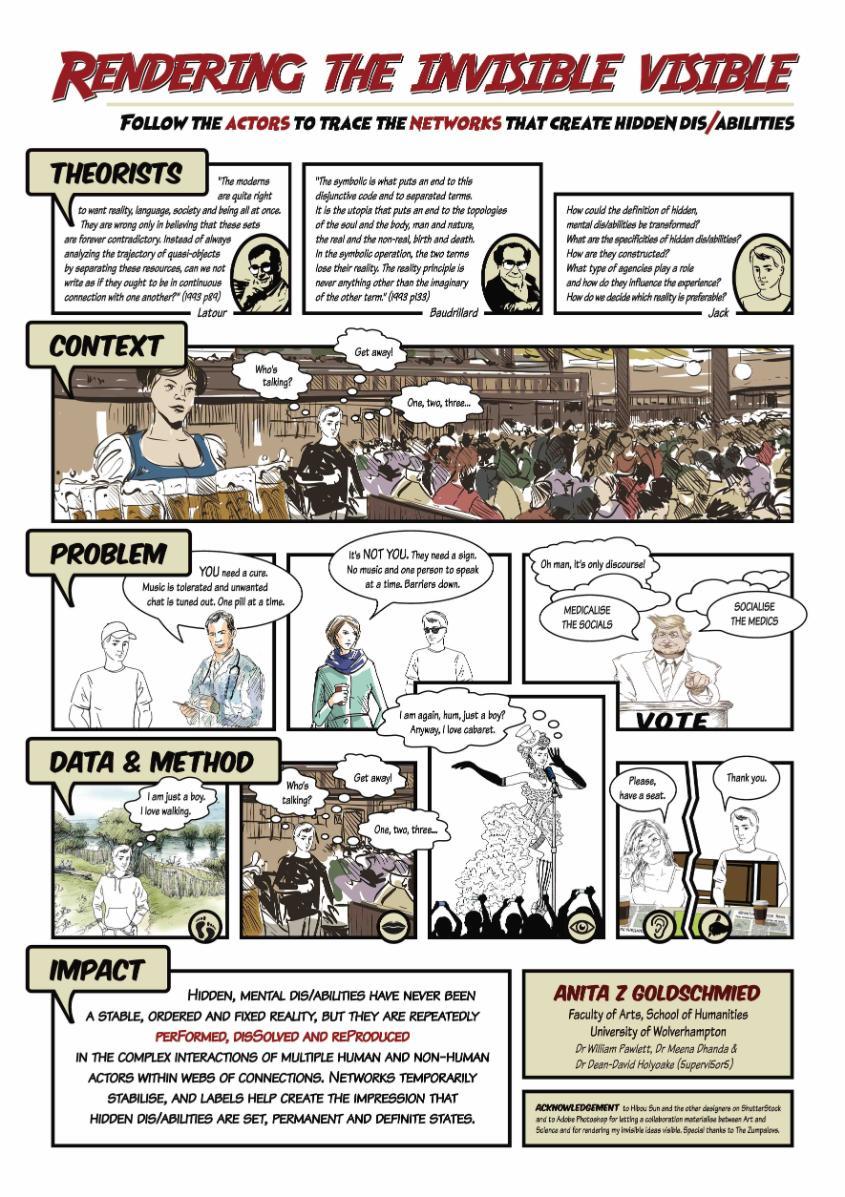

I was thrilled when local artists gave shape and form to these questions in a collaborative Art’s Council funded exhibition “Living in silence” which was created from my research data. This display showcased artist’s interpretations into artefacts including fashion, sculpture, animation, live poetry, and photography. The art destigmatised the condition of IBD in the community and raised awareness of the significant psychological distress felt by participants. As one artist said she could see how the patient is feeling and “visualise the emotions, see the beauty in something traumatic”. Foucault famously said “What strikes me is the fact that in our society, art has become something which is only related to objects, and not to individuals, or to life (Foucault, 1984, p.350). This is an example of art relating to a life with IBD:

The following poem entitled “Dr Interrupted” is an expression of my anxieties about how drastically my life has changed as I pursue my Doctorate in Health and Wellbeing.

Dr interrupted

We had made majestic plans, you and I

Who knew like leaves they too would wither and die? A glimpse, a stare, look at us in our prime

But what a sight we have now become!

We can pick up the pieces, you say Things will get better if you stay But let me go and be free

Leave me to blow away in the wind, just me!

Most times I long for days gone by

So clear it was to see the reasons why Now I fear to get caught in a gust

This is the new norm, you say, you must adjust!

Wasted, worn and wafted around

I search for rest that can never be found Though it brightens my sky

To know tomorrow will soon come by.

But it is today that I wallow and woe

I long to do so much more

Remember how we clung to hopes of bloom?

Summer was here, but left us too soon.

Poet’s rationale

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has meant that for the last seven months, as a researcher I have had to conceptualise, write and develop my data collection methodology in a creative and unique manner. Local, national and international quarantine measures have required a large scale adaptation to embrace alternative methodological approaches (Taster, 2020). Indeed, this unchartered moral territory has required a new energy to explore alternative solutions to data collection such as the analysis of personal diaries and reflections of participants to replace direct observation, poetry as self-narrative and use of online platforms (Torrentira, 2020).

References

Taster, M. (2020) Social Science in a Time of Social Distancing, London School of Economy Impact Blog, 23 March 20, available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/ 2020/03/ 23/editorial-social-science-in-a-time- of-social-distancing/ (accessed 27 October 2020).

Torrentira, M.C. (2020) Online data collection as adaptation in conducting quantitative and qualitative research during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Education Studies. 7(11) pp78-87.

Dr interrupted

Jessie Allen BSc (Hons) MPH RNLD Professional Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

Isolation

Blessing Chinganga Professional Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

Creativity and participant anonymity was a strong feature of my doctoral thesis (which I have recently submitted) and as such I developed a composite character couple to merge the participants’ stories and re-story them, as this enabled a reduction in the risk of the participant’s identities and those of their families being exposed. Gutkind and Fletcher (2008) explain that in performances that are adapted from real or fictional narratives, a composite character is often created, which is a character based on more than one individual from a story. Once the composite characters were developed I wanted to utilise their story further, therefore I wrote a children’s book as I believe that it is important for all people to see their own reflection in mainstream media. When children with same-sex parents attend healthcare settings, there are no children’s picture books that can be used as a tool to ease their fears by reflecting same-sex parents (including dual heritage) and adopted children within a hospital setting.

The book was written to address that gap and to create a status quo so that children can see their family constellation and identity reflected outside of the family itself. The book is one of positivity and inclusion and the ethnicities and genders depicted within the book are representative of the participants within my study. The professionals shown within the book are purposely gendered to challenge gender-stereotyping within professions. The book is based upon a same-sex parented adoptive family being part of the normative and what children and their parents should expect when accessing healthcare. The aim of the children’s picture book is that it can be used as an educational tool to showcase diverse families to people of all ages and it can also be used by children who have same-sex parents that are attending healthcare settings to allow them to visualise themselves and to be represented. The near culmination of my doctoral journey has seen the book accepted for publication.

References:

Gutkind, L and Fletcher, H (2008) Keep It Real: Everything You Need to Know About Researching and Writing Creative Nonfiction (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norto

A poem reflecting my thinking of the PhD journey so far. After just 18 months since starting this journey, the research study has become unruly and at times, heartbreaking. It’s been a transformative process of nurturing the research idea and the fighting the imposter syndrome that is embedded within this process. I am perplexed at how my idea becomes my teacher and I, a student of it.

You started as a simple

Sairah Miriam Shah, PhD in Education

University of Wolverhampton

“Stay home, stay safe” but what if home isn’t a safe place? COVID-19 restrictions and social distancing measures have led to more time in the home or in the same space as an abuser, increasing the risk for abuse and creating a new COVID-19 crisis. Individuals subjected to violence may be unable to reach out for help due to limited social contact, or they may not be able to seek support services or access a refuge. It's crucial we find new ways of supporting victims during this difficult time. During November 2020 I am raising money for ‘Refuge’ a charity which supports individuals experiencing domestic violence to ensure some help is there for those in need.

I am in my second year studying the Professional Doctorate in Counselling Psychology at the University of Wolverhampton. I am currently finalising my research proposal for my thesis which will explore post-traumatic growth in those who have experienced domestic violence. The negative consequences of domestic violence have been well documented, and they can be far reaching, impacting significantly on the long-term health and emotional wellbeing of those affected (McGarry et al., 2011). However, a dearth of research suggests that exposure to trauma also has the potential to catalyse a host of positive changes such as improvements in personal, interpersonal and spiritual functioning, often referred to as posttraumatic growth (Steffans & Andrykowski, 2015; Draucker, 2001; McCann & Pearlman, 1990). Studies reveal that individuals can experience growth despite enduring highly stressful environments (Linley & Joseph, 2004). I aim to carry out a longitudinal mixed method design using questionnaires and virtual interviews with individuals who have accessed support from two charities following domestic violence. This is to explore individuals’ perceptions of their recovery process and adaptation in the aftermath of domestic violence.

Personally, I have never experienced domestic abuse. One in 4 women and one in 10 men experience IPV, and violence can take various forms: it can be physical, emotional, sexual, or psychological.2 People of all races, cultures, genders, sexual orientations, socioeconomic classes, and religions experience IPV.

Long term post-traumatic growth in the aftermath of domestic violence

Nadine Denny BSc, MSc Trainee Counselling Psychologist

University of Wolverhampton

Abusive Men: A Small Attempt at Social Change

Tarnveer K Bhogal Counselling Psychology Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

I took this photo as it represents my favourite season, Autumn; symbolising the return of cosy jumpers, pumpkin spiced lattes and the wonderful colours of the leaves, as they change colour and fall. My shoes represent that I am entering into a journey of change with my Doctoral research.

Summer is over, the leaves have changed, and it is apparent that COVID-19 is not going anytime soon. As such, I have had to adapt my research into cyber-victimization experiences for adults with intellectual disabilities. This means moving my planned recruitment from advocacy centres to online. Also, moving from the data collection in the form of face to face to online interviews using the participant’s preferred online platform. Whilst, I am comfortable with online research, I am aware that there are several challenges for disability populations reflected in the digital inequalities in access and use of information and communication technologies (Chadwick et al., 2019).

Yet, I am also mindful that Autumn leaves represent hope; where change can also bring opportunity. For example, online research has the benefits of reducing barriers for research participation including financial and geographical barriers (Saberi, 2020). Therefore, from another perspective, I can promote inclusivity by opening the research to a wider geographical area, the entire UK (Alhaboby et al., 2017). With the leaves in my photo vaguely akin to the UK shoreline, and with all the different colours, I am reminded of all the inclusivity which the online platforms can provide.

References

Alhaboby, Z. A., Barnes, J., Evans, H., & Short, E. (2017). Challenges facing online research: Experiences from research concerning cyber-victimisation of people with disabilities. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2017-1-8

Chadwick, D. D., Chapman, M., & Caton, S. (2019). Digital inclusion for people with an intellectual disability. In The Oxford Handbook of Cyberpsychology.

Saberi, P. (2020). Research in the Time of Coronavirus: Continuing Ongoing Studies in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic. AIDS and Behavior, 24(8), 2232–2235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02868-4

The Season of Change

Fiona Clements Professional Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

The Covid Thesis Year, 2020!

Janet Cash Lecturer in HR & Leadership Professional Doctorate in Education

University of Wolverhampton Experiences of Business Students during Online Lockdown Learning

“Autumn leaves don't fall, they fly. They take their time and wander on this their only chance to soar.”

– Delia Owens

During autumn there is a process of shedding to bring about the new where growth and change is experienced. Akin to this, much research supports the efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) based Pain Management Programmes (PMP), however, this is based on analyses of pre-post changes in pre-defined outcome measures (Vowles, Wetherell and Sorrell, 2009; McCracken and Gutiérrez-Martínez, 2011; McCracken, Sato and Taylor, 2013). But how do individuals themselves give meaning to and experience change?

The present study explores this using Auto-Driven Photo-Elicitation (ADPE) whereby nine participants enrolled on a six-week digital PMP were invited to take a weekly photograph of a meaningful change to discuss during photo- elicitation interviews at week two, four and six. This method has gained popularity within health research and reports benefits by empowering participants to discuss and reflect upon what is individually meaningful, portray what may be difficult to express in words and explore everyday life that may be taken for granted or overlooked (Balmer, Griffiths and Dunn, 2015). Thematic analysis was used to analyse the transcripts and preliminary themes created. Findings support the use of ADPE as an engaging and valuable method for helping individuals with persistent pain conceptualise and articulate their pain management journey.

Alongside my participants I have used photography to capture and reflect upon my own research journey (Figure 1).

References

Balmer, C., Griffiths, F. and Dunn, J. (2015) A review of the issues and challenges involved in using participant-produced photographs in nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(7), pp.1726-1737.

McCracken, L. and Gutiérrez-Martínez, O. (2011) Processes of change in psychological flexibility in an interdisciplinary group-based treatment for chronic pain based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(4), pp.267-274.

McCracken, L., Sato, A. and Taylor, G. (2013) A Trial of a Brief Group-Based Form of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Chronic Pain in General Practice: Pilot Outcome and Process Results. The Journal of Pain, 14(11), pp.1398-1406.

Vowles, K., Wetherell, J. and Sorrell, J. (2009) Targeting Acceptance, Mindfulness, and Values- Based Action in Chronic Pain: Findings of Two Preliminary Trials of an Outpatient Group-Based Intervention. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16(1), pp.49-58.

Adjusting the Lens on Change during Acceptance and Commitment Therapy based Pain Management

Suzanne Roberts BSc (Hons), PG Dip, MSc, MBACP, RN 4th Year Post Graduate Research Student

University of Wolverhampton (Professional Doctorate in Health and Well-Being)

Dr Debra Cureton, Professor Megan Lawton and Dr Sarah Sherwin

Your course reflects passage through the sea, the ebbs and flows, ripples and waves

September 2018 ,A starting point ;gazing out in the calm blue waters, sun glinting on ripples mirroring the jewels of promise, reflecting the riches to come

Riding the waves of life, love and study, keeping afloat in your own personal boat Yet the clearest summer sky can change and then comes the rain

Ripples of anxiety and strife, rocking the boat, mirroring student life

Fishing for riches of study and practice success, angling for a catch and reward

Sometimes coming up empty, the crushing defeat of failure and casting out again in the hopes of resubmission moving forward

Then came the tsunami, the crescendo of COVID, your boat is capsized, unexpected, brutal, Unprecedented, unforgiving and unrelenting, a tidal wave of fear and death,

Leaving destruction in its wake

Forcing you to make choices in the flow, which way do you go

Which channel do you follow, agonies abound, and the conflicts in life create indecision and strife But you survived, you’re alive, changed, enriched, you have clambered back on board

You will all eventually get your reward; reach an oasis of calm, gently rocking in the waves Gather up, prepare, get ready for the next adventure and caper

Mentors and tutors have been guiding you to shore, away from the rocks, a beam of light illuminated your plight

We helped you navigate your way through choppy waters, the beam shining bright, perils are ignored, the path is made clear and free from harm

Go forward, share lessons learnt, wisdom gained, in practice strive for change , support and transform

We have taught you to be a lighthouse in someone else’s storm

The Voyage of M18

Tracy Lapworth Professional Doctorate in Health and Well-Being

University of Wolverhampton

In my attempt to interview grandmothers who had sick grandchildren in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), I visited two NICU in the West Midlands at grandparents’ visiting times in the hope of recruiting participants for my study. In my naiveté, I assumed that there would be an abundance of grandmothers visiting their sick grandchildren on a regular basis. What I discovered instead, was that there were no grandmothers visiting either in the afternoon, evening or at weekend visiting times. These are two poems I wrote whilst I sat for many hours waiting for any grandmother to visit her grandchild.

Poems for the grandmothers who were not there.

‘Behind the scenes’: Grandmothers as silent heroes in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Hilary Lumsden Professional Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

I have been collecting data from the study participants (millennials) on what the millennial generation apparent self-care looks like as part of my doctoral research. Until recently, I was ignorant of the possibility of the use of art based methods for health research (Norris 2020; Boydell et al 2016).

As I collected and reflected on the story artefacts, I began to appreciate the richness of this method. This made me to feel that qualitative studies help to access rich data that is normally unavailable or unacceptable for quantitative research (Bast et al 2013; Cross and Holyoake, 2017; Townsend et al, 2006). I am now in love with the use of art-based methods in doing health and wellbeing research. This is however a new experience for me as my previous research was laboratory based and driven by positivist considerations. I had always believed that a phenomenon must be about cause and effect and thus objectively measured. That for me was being “scientific”. But there is so much to explore and know about the meanings of apparent self-care than the restrictions of scientism would allow (Crawford 2017; Alexander et al 2014).

The use of both textual and graphic data to construct meanings of the social reality of people will help creativity and the unpacking of many interesting concepts in health and wellbeing. I have been reflexing a lot and feel that scientism had imprisoned me seriously in the past and gave me no space to explore social phenomena interpretively (Jiang 2018; Baron, 2019).

References

Alexander G., Duarte A., García-González, L., Moreno,M.P. and Fernando D. V. (2014) "Implications of Instructional Strategies in Sport Teaching: A Nonlinear Pedagogy-based Approach." European Journal of Human Movement 32 (2014): European Journal of Human Movement, Vol.32. Web.

Baron, C. (2019) "THE RISE, FALL, AND RESURRECTION OF (IDEOLOGICAL) SCIENTISM." Zygon 54.2: 299-323. Web.

Bast, A., Briggs, W.M., Calabrese, E.J., Fenech, M.F., Hanekamp, J.C., Heaney, R., Rijkers, G., Schwitters, B. & Verhoeven, P. (2013) "Scientism, Legalism and Precaution - Contending with Regulating Nutrition and Health Claims in Europe", European Food and Feed Law Review : EFFL, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 401-409.

Boydell, Katherine M, Hodgins, Michael, Gladstone, Brenda M, Stasiulis, Elaine, Belliveau, Burton, J. K., Moore, D. M. and Magliaro, S. G. (1996) ‘Behaviorism and Instructional Technology’. in Handbook for Research for Educational Communications and Technology. New York, N.Y.: Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

Crawford, R. (2017) "Rethinking Teaching and Learning Pedagogy for Education in the Twenty- first Century: Blended Learning in Music Education." Music Education Research 19.2: 195

Cross V, Holyoake D.D. (2017) ‘Don’t just travel’: thinking poetically on the way to professional knowledge. Journal of research in nursing. 22(6-7):535-45.

Jiang, Z. (2018) "Is the 'Intention' There? On the Impact of Scientism on Hermeneutics", European Review, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 381-394.

Norris, J. (2020). A Walk in the Park: A Virtual Workshop Exploring Intertextuality and Implicit Powers Within Texts. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 20(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708619885413

Townsend A, Wyke S, Hunt K (2006). Selfmanaging and managing self: practical and moral dilemmas in accounts of living with chronic illness. Chronic Illn. 2:185– 194.

Knowing Differently My Experience of Collecting Story Artefacts as Data for Health Research

Jacob Enemona Professional Doctoral Student in Health

University of Wolverhampton

All aboard!

Janet Mortimore Professional Doctoral Student

University of Wolverhampton

Doctoral process is a long and isolated degree

Still, we wanted to enter this course before our teaching could reach to its silver jubilee. We knew our professional practice and professional ideology has friction

Our positionality needed a new insight, became our mission

The very mental itch that has been bothering us at work

Following school’s policy, DfE guideline and Ofsted framework

Often put us into thoughts and forced into looking for reasoning

Always tried to search for sound answers however very weakening

First phenomenon, why do we divide students into ability grouping

We view this practice and considered it, quite educationally, polluting

Registering ourselves for a doctoral degree and delve into this phenomenon

We thought policymakers need to borrow researchers’ perceptions and related epiphenomenon

The other phenomenon under investigation

Is about the school leaders and upon them all the allegations

Whether it is instructional leadership, transformational style or other leaders’ traits

We develop interest in exploring true leader’s practice and debate

Ah! that first module really shifted our belief

The doctoral process was a challenge! and it was not such a relief

What is positionality, ontology and epistemology, did you say?

It was only Cresswell, Brayman and Silverman, who stopped us going stray

Eventually, started to like the philosophical thinking process

Even though failed in first assignment but learnt how to access

The wider resources, the valuable discourse with our module tutors

Those long doctoral sessions in Wolverhampton University was an investment for future

The EdD WhatsApp group appeared to be such a buddy

The complexity of assessments diminished, and we learnt how to study

Delving into literature for module two, was an assignment

our perceptions began to receive alterations, and thoughts oozed out of old confinement

It, didn’t end here, before entering into the thesis stages

Module three was designed to record students’ understanding using distinct

gauges Use of artefacts, reflection and dialogue with other community of practice

This assignment certainly aligned effectively, great were assessment tactics

The three years’ worth of work is gradually making us a research native

We have learnt to innovate the existing phenomenon without being

imitative Critical analysis, evaluation and art of understanding methodology

Let us bet you; you will never find a creative course that may outmode your epistemology

Eye opening is the shift in our philosophy and identity

We grew confident that our research will bring professional serenity

Our views and beliefs have improved, rebuilt, reshaped and have got new features

We were fortunate, that our university has such great teachers

Don’t mistake us, not only the perceptions and views

The whole thinking pattern has reshuffled but some queries remain in queue

Evident is drastic innovation in academic writing and critical thinking

Little had we ever imagined that our queries will begin shrinking.

Doctoral Journey ……….

Ambreen Alam and Muhammad Zubair, EdD 4th Year Professional Doctorate Students

University of Wolverhampton

Abstract

This article aims to discuss the need for clinical education to embrace the use of narrative. It discusses the split – most evident in Anglophone countries – between the arts and the sciences, before discussing what can and cannot be known from the scientific method, and what can and cannot be known from narrative approaches. It concludes that narrative is the natural way to teach and learn and has the advantage that it can explore hypothetical situations in safety as well as both to learn and to convey values and attitudes while the hypothetico-deductive method can say what does happen but can shed no light on what should happen.

Introduction

Eva (2014) reminds us how Lasagna’s (1964) revision of the Hippocratic Oath tells us that ‘there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug.’ (Lasagna, 1964: p11) In the course of this article, we consider how science and the arts were once wedded, before splitting in a manner which, most evidently in Anglophone countries, rendered them almost as strangers to each other. We move on to discuss in detail the need for narrative in clinical education and how this can be beneficial to teachers, learners, and patients and their relatives by permitting an exploration of ‘emplotment’ and hence hypothetical situations with full cognisance of all the actors and the impact of the scenario upon each and this in all its diverse manifestations.

Science and the arts

For a Renaissance scientist, there could never be any question of a division between the arts and the emergent sciences. Whether da Vinci, Harvey, Paracelsus or any of their contemporaries, the simple need to communicate their findings not only to their peers but more especially to their patrons meant that they had not only to be scientific in the sense of their explorations but also artists both in the sense of the graphic depiction of their work and in the verbal descriptions. An outstanding example of such versatility is Girolamo Cardano, physician by trade, but who produced in the course of the 16th century highly influential texts on ‘medicine, astrology, natural philosophy, mathematics, and morals … [and on] devices for raising sunken ships and stopping chimneys from smoking’ (Grafton, 2002: pxii) and whose Book of my Life (Cardano, 2002) gives an insight into how minds such as his worked.

It is in some senses ironical that the scientific descendants of these Renaissance minds might well find them somewhat unnecessarily verbose, elaborate and even obscure. The Renaissance man, and to a large extent woman, lived the ideal of the generalist who could reliably move in and out of diverse circles and engage in meaningful discussion across the full range of human experience and contemporary knowledge.

Even as late as the Long Eighteenth Century could we find such eminent figures as Dr Samuel Johnson – a doctor of letters and not medicine as physicians had not yet gained a pre-eminence over the title (Hamilton, 1981; Strathern, 2005) – whose 1773 edition of his dictionary (first published in 1755) had an entry for the word science which he pointed out was derived from the Latin word scientia meaning knowledge (Johnson, 1773/1828). He then lists the meanings of the word science in his times as follows (Lyons, 2001).

- Knowledge

- Certainty grounded on demonstration

- Art attained by precepts, built on principles.

- Any art or species of knowledge

- One of the seven liberal arts, grammar, rhetorick, logick, arithmetick, musick, geometry, astronomy

These liberal arts were close to the Medieval Trivium and Quadrivium which every aspiring Medieval physician who attended university [although most did not] would have studied prior to undertaking his [and almost never her] medical studies in a higher faculty. That the medical student would be Master of Arts prior to studying medicine was no coincidence as the Trivium and Quadrivium were deemed essential for the proper understanding of any learning in a higher faculty, whether this be Medicine, Law or Theology. The Arts were the gateway to further study and only by demonstrating a basis in them could be aspiring university-trained physician proceed further (Matheson, 1999).

It is notable that Dr Johnson includes both what we would now recognise as science and the liberal arts under the same heading. The split came much later with the term scientists coined in 1834 in contrast to artists as students of the material world (Whewell, 1834) and by 1977, the fourth edition of the Penguin Dictionary of Science has only physics, biophysics, astronomy, chemistry, biochemistry, molecular biology, and mathematics and computing listed under science.