When Christmas Stopped The War….

28/08/2025 - 4.39

Roger Slater

The deadlock on the Western Front continues and the rival armies face one another in sodden trenches, sometimes not more than forty yards apart. At the outset, neither France, Great Britain or Belgium was ready for the war on land. Britain had its Expeditionary Force fully prepared but it was soon to realise that in place of hundreds of thousands of men, millions would be required. These are now being enrolled, drilled, armed and despatched.

The premature policy of breaking the dykes and flooding the country – a policy which should never have been adopted – has made much of Flanders a marshland, causing the trenches to be half full of water all the time. A dreadful harvest of disease will inevitably be reaped by all Europe from these months of Winter exposure, from the almost innumerable dead whose bodies congest the hastily dug pits, and from the armies of wounded everywhere. Already signs are evident of this...

The War Illustrated (edit) January 1915

Despite the images available in books and on the internet, (and even on the silver screen – Joyeux Noel is worth a watch if not completely factual) it's hard to imagine what Christmas 1914 was like in the trenches on either side. This after all was Christmas in a war that was going to be over by Christmas, and it was a war like no other before or since. It was a siege that had become a stalemate fought in what through continuous cold and rain had become semi liquid mud - all that remained of Flanders and Northern France. The British troops had fought their way through the first battle of Ypres, the shattered units and battalions that remained relieved in November by the French, only to find themselves re-building in the trenches, in some cases only 40 yards from their enemy, not only dodging the bullets and shells, but within earshot, even able to smell their opposing cookhouse. Close enough that with typical sardonic humour, the opponents would shout insults to each other and would even stick up small wooden signs saying ’missed’ or ‘left a bit’ after a volley of shots or machine gun fire.

These were ordinary men who had, four months earlier been living ordinary lives. But for chronology it could have been any one of us in the trenches. If you were born male in Britain, Germany, France or Russia in the years 1887-97, it was odds on that you would spend Christmas knee deep in mud, rats and lice while waiting for your turn to play hide and seek with rifle or machine gun bullets.

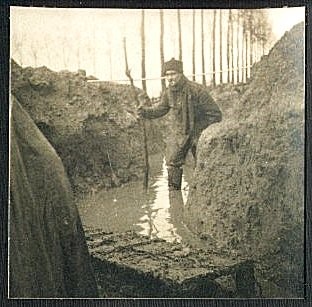

Life in the Trenches. Source: Author's Collection

Standing sometimes up to your knees in the slime of a waterlogged trench it’s Christmas Eve on the Western Front. Stooping, you wade across to the firing step and take over the watch from a bedraggled but relieved comrade. A comment, an answer, maybe something to look out for and a shared cigarette, then your bleary-eyed and mud-spattered colleague shuffles off towards his dug out and it is your turn in the firing line. Stamping your feet to keep warm, morale is raised as you believe that in the New Year the march to victory will finally begin – then it is lowered as you remember that this is the war that would be over by now. You’d be back at home with your family… It was the point where the armies from both sides began to realise that they had been duped. Few soldiers from either side had any personal grievance against the enemy and the stalemate and conditions of trench warfare cried out for relief. Indeed, that up-rushing of relief garnered substance to what followed and was in itself responsible for some of the confusion, romantic exaggeration and myth that surrounds the truth of the Christmas Truce.

On Christmas Eve, 94 British soldiers were lost to snipers and minor skirmishes along the Western Front and the German Army had lost a similar number. Despite the date, there was no formal end to hostilities on either side. It was very much an organic affair that in some areas along the twenty-seven-mile front between the Ypres Salient and La Bassee hardly registered a mention, yet in other areas it left a profound impact upon those who took part.

Subsequent letters home contained rushed and contradictory accounts and Battalion Histories and other reports written in the following months and years were often unintentionally embellished with both propaganda and hindsight, yet the facts (as best as we can understand them) still inspire awe and amazement at the ease at which arms were laid down. Those uncertain first steps towards a foe and the potency of human nature that created an un-orchestrated few moments of peace in the midst of the greatest conflict the world had ever seen.

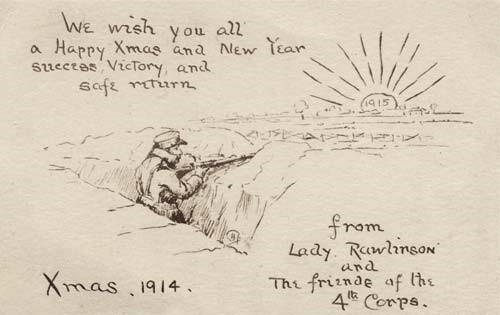

As Christmas approached parcels from home began to arrive from families, friends and also from the state. Food was surprisingly plentiful in the British lines, with stories of Turkey, Geese, Duck and Plum Puddings later recounted in letters home, and each soldier also received a 'Princess Mary box'; a metal case engraved with an outline of George Vs daughter filled with chocolate and butterscotch, cigarettes and tobacco, a picture card of Princess Mary and a facsimile of George Vs greeting to the troops. 'May God protect you and bring you safe home,' it said. With shorter lines of supply and much more direct links to the Fatherland, the German Regiments were well stocked generally and at Christmas they were not to be outdone, soldiers receiving a present from the Kaiser, the Kaiserliche, a large Meerschaum pipe for the troops and a box of cigars for the NCOs and officers. The Belgians and French also received parcels but for them there was a greater level of sadness as their countries were occupied, this the likely reason that there was far less evidence of truce in their sectors of the lines than those held by the British.

The Daily Telegraph reported that in one area, the Germans had managed to slip a chocolate cake into British trenches (though there is little to corroborate this) and the report continued that it was accompanied with a message asking for a ceasefire later that evening so the Germans could celebrate the festive season and their Captain's birthday. They proposed a concert at 7.30pm when candles, the British were told, would be placed on the parapets of their trenches. Whether or not this is fact or fantasy remains to be seen.

What we do know is that each German unit along the lines received an influx of mini Christmas Trees in ‘care packages’ from home and on Christmas Eve many of these were placed along trench walls and lit with candles.

A Christmas Tree in a German Trench. Author's Collection

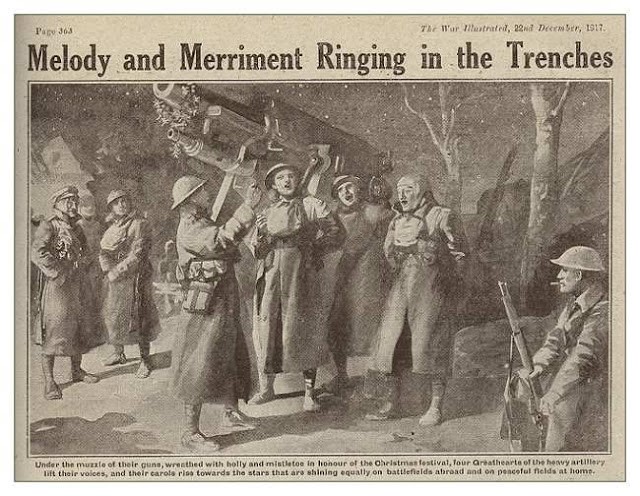

In many cases (as recorded by British soldiers in their diaries and letters) as the candles were lit, the Germans apparently started to sing traditional Christmas Hymns and Carols in their trenches. With artillery silent and the weather breaking, Tannenbaum (Oh, Christmas Tree) was heard to drift across no-man’s land to surprised and a little confused British infantrymen. The sight of the trees and candles was reported along the lines from the observers and scouts on their firing steps, and despite the wariness of the officers, curious heads began to pop above the parapets to take in the spectacle of sight and sound in the darkness. Slowly, from the British trenches carols were sung in return and when the Germans finished there was spontaneous applause from one side to the other.

Melody and Merriment Ringing in the Trenches. Source: The War Illustrated

By late evening the British high command (entrenched in a luxurious châteaux 27 miles behind the front) had begun to hear of the fraternization and stern orders were issued by the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, Sir john French against any such behavior citing the consequences of parleying with the Germans.

That became the perfect excuse for the opponents to start shouting to one another, to continue the singing and, in some areas, to suggest a truce – some Germans were known to have placed signs on their trenches alongside the trees with ‘No Fire’ and ‘You no fight, We no fight’ written on them for their foes to see as dawn broke on Christmas Day. Along the trenches as the sun rose on a frost covered Christmas morning, somewhere a first soldier stood up and offered himself as a target to the snipers, yet no shot was fired.

There are numerous records and reports of Germans appearing as shadows in the dawn mist walking slowly into no-man’s land beckoning toward the British lines and in broken English encouraging the Tommies to do the same, there are also numerous reports and records that in fact, the fraternization started earlier. Regimental Sergeant Major Beck of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment put in his diary for Christmas Eve that:

“...it was a quiet day. Germans shout over to us and ask us to play them at football, and also not to fire and they would do likewise. At 2am (Christmas Day) a German band went along their trenches playing Home Sweet Home and God Save the King which sounded grand and made everyone think of home. During the night, several of our fellows went over no-man’s land to the German lines and were given drink and cigarettes”.

Sir Edward Hulse, a Captain in the Scots Guards recounted his memory in a letter home to his family:

“Four unarmed Germans approached at 08.30. I went out to meet them with one of my ensigns. Their spokesmen started off by saying that he thought it only right to come over and wish us a Happy Christmas, and trusted us implicitly to keep the truce. He came from Suffolk where he had left his best girl and a 3 ½ h.p. motor-bike!”

He continued that having filed a report at headquarters, he returned at 10.00 to find crowds of British soldiers and Germans out together chatting and larking about in no-man's land, in direct contradiction to his orders. His concern was less about the fraternization than it was the fact that his orders had been disobeyed and he sought out a German officer, making arrangements for both sides to return to their lines.

Throughout, however he listened and watched the scene before him and his letter continued:

“'Scots and Huns were fraternizing in the most genuine possible manner. Every sort of souvenir was exchanged addresses given and received, photos of families shown, etc. One of our fellows offered a German a cigarette; the German said, "Virginian?" Our fellow said, "Aye, straight-cut", the German said "No thanks, I only smoke Turkish!"... It gave us all a good laugh.”

Festive Message 1914. Source: Author's Collection

There are numerous reports of soldiers from both sides slowly crossing the desolate space between the lines. In many areas, the truce started with an agreement that both sides could recover and bury their dead, only once these tasks were underway did the fraternization begin as soldiers attended the simple burials of comrades and enemies alike, before exchanging thoughts and good wishes in broken conversation. Men exchanged gifts of cigarettes, chocolate, beer and rum and souvenirs – buttons and even badges from their uniforms. In one or two places soldiers who had been barbers in civilian times gave free haircuts and its recorded that a German, a juggler and a showman in civilian life gave an impromptu, and given the circumstances, somewhat surreal performance of his routine between the trenches in no-man's land.

It is certain that the truce was effected over a large area as there are many photographs that show the opposing infantry together, even with mixed and matched uniforms as caps and helmets were swapped. Indeed, over the following months of early 1915, a great deal was written in letters and diaries by soldiers about the truce yet many officers denied that it took place and it is not mentioned in Regimental Diaries or Histories. The ephemera and souvenir collections perhaps testify the reality.

There is no doubt also that in some areas there were football matches – both between the two sides and also where one side staged a match for the other to watch, each more informal kick-abouts than a match, some reports even saying that upwards of 80 men played. The most famous – or at least most referred to of these, was the match apparently played at Ploegsteert, known to the British troops at the time as Plug Street, some two miles north of Armenitieres.

These days the area broadly between the N365 and the N515 is a guaranteed stop for most of the Great War Tours as there are a number of Commonwealth Cemeteries nearby as well as the Memorial to the Missing and in the wood itself, the remnants of the very trenches defended at Christmas 1914. On the back-road that leads to the much smaller Prowse Point Cemetery is the Khaki Chums memorial. A simple wooden cross accompanied by a plaque that commemorates La Treve de Noel and a football match. It is often adorned with colours, scarves and modern-day match balls left by visitors despite doubts that any match was ever played here, however it does identify the most northern point where the Christmas Truce took effect.

Khaki Chums Memorial. Source: Author's Collection

Cigarettes swapped, hands shaken, perhaps a game of football was played on the shell pocked land somewhere. As the story goes, the Germans won 3-2. This fabled match is recorded as hearsay in those diaries and letters, and on January 1, 1915, the London Times published a letter from a Major in the Medical Corps reporting that in his sector the British played a game against the Germans opposite and were indeed beaten 3-2. Similarly, Kurt Zehmisch of the 134th Saxons recorded in his diary:

“The English brought a soccer ball from the trenches, and pretty soon a lively game ensued. How marvelously wonderful, yet how strange it was. The English officers felt the same way about it. Thus Christmas, the celebration of love, managed to bring mortal enemies together as friends for a time.”

His is among few references in German records that also give a scoreline of 3 – 2 to the Hun, however a little research through the Battalion Histories shows this to be ambiguous. Were the two sources referring to the same match? Was it hearsay or did they actually witness a match themselves? The fact that both sides reference a game that ended 3 – 2 can surely only be coincidence as geography proves that they cannot have been one and the same game; not only were the respective units some distance apart, they were on opposite sides of the River Lys! What remains equally as strange – bearing in mind how momentous an occasion a match would have been, is that among all the photographs of the soldiers from both sides intermingling, there are no pictures of this or any other match.

Fraternising with the Enemy! Source: Author's Collection

In fact, the photograph used below (and likely to be being used in many, many other documents, websites and frustratingly, news reports on the day when ‘Football Remembers’ every year) was taken at Salonika, Greece on Christmas Day 1915. Look closely and you may realise that both ‘teams’ are in British uniforms! Not a surprise really as it features a match between the Officers and men of the 26th Divisional Train.

Football in Salonika. Source: Author's Collection

It must also be remembered that although the truce was widespread it was not total. In some parts shelling and firing continued. There were deaths on Christmas Day 1914 and there are graves in a number of Commonwealth Cemeteries in Northern France that attest to this. A soldier, Pat Collard wrote to his parents describing his horrendous Christmas under fire. The letter closed:

“Perhaps you read of the conversation on Christmas Day between us and the Germans. It's all lies. The sniping went on just the same; in fact, our captain was wounded, so don't believe what you see in the papers."

It was published in the Hampshire Chronicle in mid-January 1915.

Where the truce was established, it lasted (at least) all day. In some places an immediate agreement had been reached on a set time when the troops would return to action, or on a signal from one side or another. Captain J C Dunn, a Medical Officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, whose unit had fraternized and received two barrels of beer from the Saxon troops opposite, recorded how hostilities re-started on his section of the front:

“At 8.30 I fired three shots in the air and put up a flag with Merry Christmas on it, and I climbed on the parapet. The Germans put up a sheet with Thank You on it, and the German Captain appeared on the parapet. We both bowed and saluted and got down into our respective trenches, and he fired two shots in the air, and the War was on again.”

In other areas the truce lasted for three or four days and there are thinly substantiated stories that in one or two places, the truce, or at least a distinct lack of aggressive behavior, was recorded well into the New Year.

Whether or not the truce was seen as a means to spy on opponent’s positions or was indeed a token of peace by simple men who wanted to end the slaughter is a matter of opinion. The mythology associated with the truce of Christmas 1914, has now far outlived any first-hand knowledge of the events and we are left to consider the records that remain. Whatever your thoughts, it must be comforting to know that regardless of reason or intent and the propaganda of hate, simple men could still lay down their arms and extend the hand of peace and goodwill…

Biography

Roger Slater was born in Harrow in the late 1950s and has moved around a bit and retired to Devon with wife of 24 years, Helen. He originally trained as an Electrical Engineer but worked for almost 40 years in Building Services Technologies, primarily HVAC control systems and Electronic Security. Roger retired in 2018 having run his own Engineering Consultancy for almost 15 years.

For relaxation and hobbies, he writes, mainly about his football club, Wealdstone FC and has published eight books including a club history since 2002. He does not class himself as a historian, just an enthusiastic amateur.

He also writes for a fanzine/magazine called Where’s The Bar that has just relaunched.

Otherwise, hobbies are upcycling and building ‘strange’ lighting out of people’s rubbish and occasionally painting, though he also buys and sells at auctions and on the internet (mainly football related or antiques).

In respect of other sports, he will watch most but follows the Toronto Blue Jays avidly in baseball, as a result of working on and off in Canada in the early nineties.

Roger also reads and collects books on World War One, in particular personal biographies and war diaries as opposed to battle histories…

All of that could change tomorrow or on any other day if something else takes his fancy as he will give most things a try if they appeal!!

Every Picture Tells a Story…

03/09/2025 - 3.01

Roger Slater

That’s what Rod Stewart would have us all believe anyway, however what follows may just go some way to proving his point. As you know, I love my football – especially the quirky bits which is probably why I follow Wealdstone) and I love things about World War One and Two, particularly if there’s a football link. This then, hits the spot.

While doing some research on Prisoners of War with a football link outside of Great Britain, I came across two names, Jean Prouff and Julien DaRui. Each had a similar though separate story, yet each story also came together…

At the invasion of France in August 1939, a large number of eligible Frenchmen were conscripted into the French Army and this included a number of sportsmen. At the time Julien Darui was the French International goalkeeper, despite having been born in Oberkom, Luxembourg, during World War One of Italian and Portuguese parents. The family emigrated to France when Julien was a young child and the fact he grew up there seems to have satisfied the criteria for qualification not only for the National Team but also for National Service!

Just before his twentieth birthday, he made a playing debut in goal for Olympique Charleville where he made 47 appearances over a couple of seasons before joining Olympique Lillois where he played until May 1940. At that point he joined the army (though whether this was conscription or choice is unclear). After basic training, he found himself in Northern France as part of the French Army, defending the British Expeditionary Force’s retreat to Dunkirk, at which point he was captured by the German Army and held as a Prisoner of War.

Not for long as it turned out, as while awaiting transfer from France to a camp likely in Germany or Poland, DaRui escaped, or more accurately, he seems to have walked out of the camp in Northern France and (obviously being fluent in the language helped!) he went home. One conscious decision he seems to have made when he got home however, was to not rejoin the football club he had played for at the outbreak of war, Olympique Lillois, instead joining another local side in Red Star Olympique where he remained for a couple of years. (In the meantime, France had signed an Armistice with Germany). From Red Star, he had a mandated move to Lille (of whom Lillois had been a forerunner) when the French FA stated that all players had to return to their pre-war clubs. He moved on again later in the war and most notably, in 1945, he joined CO-Roubaix-Tourcoing where he was to make 234 appearances. He later moved on again to Montpellier where he eventually retired from playing after circa 400 appearances for his clubs and twenty-five International Caps gained between 1938 and 1951, figures that no doubt would have been greater if war had not intervened. Hold that thought for a moment.

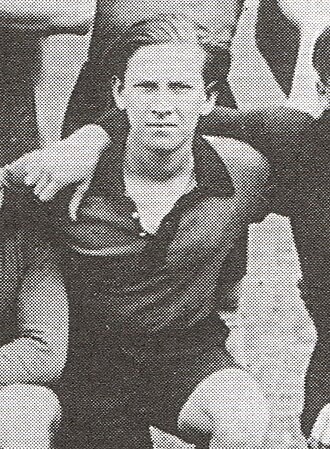

Julien DaRui, 1947. Source: CO-Roubaix-Tourcoing

Jean Prouff has a similar story. Born a few years later in 1919, in Peillac, south-west of Rennes, his family moved to the city when he was a youngster. It was there he first played football and he eventually joined Stade Rennais Universite Club at the age of 14. An all-rounder, he also played Rugby and excelled on the athletics track, but his passion for football was paramount and his performances in midfield were gaining notice. In 1935, with the side now known as Rennes, he was the young star performer in the Coupe de France des Espoirs as the young side ran out winners 5-1 against…Red Star, and Prouff scored twice.

Jean Prouff, 1935. Source: Stade Rennes FC

A year later and the family had moved to Nantes due to his father’s work and Jean signed for SC Fives, a forerunner of the modern-day Lille side which was formed when FC Fives and Olympique Lillois merged in 1944, but shortly after he signed his first contract, war broke out. Prouff like DaRui was drafted into service and he was assigned to a Military Engineers regiment in Northern France, who coincidentally happened to have one of the best military football teams.

Fighting the Germans in Eastern France In 1940, with his unit defending the Maginot Line, Prouff was captured and taken prisoner. As with DaRui, he was only a captive for a short time as he managed to escape. He then walked over 400 kilometres, seemingly unchallenged to Paris!

He did return home and to his former club in Nantes before re-joining Rennes in 1941. That was short lived as the French Football Federation (you’d think they’d have other things on their mind?) mandated that all players must return to the clubs they were signed to before the start of the war, as with DaRui, Prouff was ordered to return to his former club, SC Fives. He was only back there for a year before the Federation again made sweeping changes by assigning players across the new regional teams which had been created, with Prouff joining the Breton team in Rennes.

It seems that neither player was recalled by the French Army, and with the armistice signed with Germany, they could not be re-captured and held prisoner. Lucky escapes indeed as under the terms of the armistice, French Prisoners of War had to remain prisoners until a Peace Treaty was signed, and many found themselves in forced labour camps in Germany and Poland for the duration of the war in Europe. DaRui and Prouff were able to continue their careers throughout hostilities. Prouff also played international football for France, making 17 appearances between 1946 and 1949.

Following the liberation of France in 1944, the cities of Rennes and Nantes found themselves free and with the football teams starting to reshape themselves into more recognisable teams and leagues, DaRui and Prouff found themselves called up to a National representative team.

The match was to be a celebration of Liberation, a Great Britain side (drawn from the British Army) set to play an unofficial International on the 30th September 1944, against the (equally unofficial) French National XI. DaRui seems to have made his way to the Parc du Princes, Paris, for the match with no concerns, but Prouff was unable to secure transport, so he decided to cycle the 200 miles from Rennes to Paris, succeeding in reaching the capital within two days and little more than a couple of hours before the start of the game. His fitness was not to be questioned though as he then went onto the pitch with his teammates to warm up for the match despite the journey, though teammate Darui is reported to have said “…you have the nerve to warm up before the game when you have just cycled 300km?”

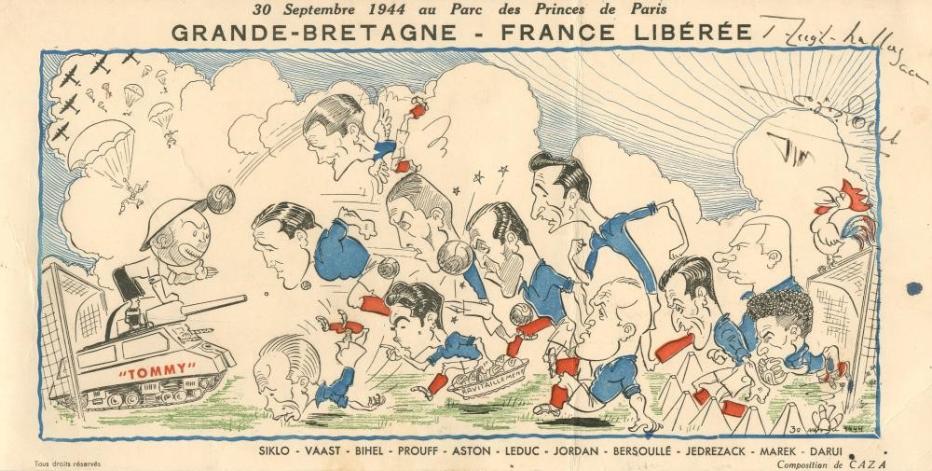

That is the story, and this is the picture:

Cartoon From The Match. Source: Author's Collection

A wonderful cartoon drawing of the French Team from the match that came up in a search online, the original image having been sold in an auction. I wonder still if the depiction of the British Tommies in their tank under a sky full of the D-Day Invasion paratroopers was noticed by the French, in particular the two players in the French XI that had, all be it for a short time, been Prisoners of War?

You may also notice two signatures on the original image in the top right? They are (below) Sir Stanley Rous, a name you will surely know from ‘football circles’ as the Secretary of the Football Association for almost 30 years and subsequently the 6th President of FIFA. Above his signature, is that of Air Chief Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Commander of No12 Fighter Group during The Battle of Britain. He was killed when his plane crashed just six weeks after the match on 14th November, 1944. Perhaps there’s another story there…

Note:

This article was first published in the football fanzine - Where's The Bar? If you would like to find out more about the fanzine and be able to order back issues as well as the current issue, go to: https://www.wheresthebar.co.uk/

Biography

Roger Slater was born in Harrow in the late 1950s and has moved around a bit and retired to Devon with wife of 24 years, Helen. He originally trained as an Electrical Engineer but worked for almost 40 years in Building Services Technologies, primarily HVAC control systems and Electronic Security. Roger retired in 2018 having run his own Engineering Consultancy for almost 15 years.

For relaxation and hobbies, he writes, mainly about his football club, Wealdstone FC and has published eight books including a club history since 2002. He does not class himself as a historian, just an enthusiastic amateur.

He also writes for a fanzine/magazine called Where’s The Bar that has just relaunched.

Otherwise, hobbies are upcycling and building ‘strange’ lighting out of people’s rubbish and occasionally painting, though he also buys and sells at auctions and on the internet (mainly football related or antiques).

In respect of other sports, he will watch most but follows the Toronto Blue Jays avidly in baseball, as a result of working on and off in Canada in the early nineties.

Roger also reads and collects books on World War One, in particular personal biographies and war diaries as opposed to battle histories…

All of that could change tomorrow or on any other day if something else takes his fancy as he will give most things a try if they appeal!!

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/iStock-163641275.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/250630-SciFest-1-group-photo-resized-800x450.png)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/Judo.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/Nikhil-Seth-honorary-professorship.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/241014-Cyber4ME-Project-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/City-courtyard.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images/stock-images/Wulfuna-Building-sunny-day---news-teaser.jpg)