A Labour of Love

28/10/2024 - 1.47

David Proudlove

Even as a young boy, I always associated football with work and industry, and for my friends and I, it was central to our lives in the Potteries village in which we grew up. My dad was a pottery worker, and football was his escape, and so as my interest in the game developed, it became something that we shared.

My nan often referred to me as ‘Mr. Inquisitive’ as once something had caught my attention, I absorbed myself in it, and that was certainly the case with football, collecting the Panini stickers and devouring Football Weekly with Dad. And that inquisitiveness led me to pepper the old man plenty of football related questions.

One of the first was, ‘…dad, why are Arsenal called Arsenal?’ Well, the answer may seem like quite an obvious one, but I was five years old at the time, and in any case, there is quite a bit more to it. But in short, Dad told me that Arsenal were born in a munitions factory, hence their militaristic nickname. Moving on from Arsenal – which we did quickly as Dad disliked Arsenal due to the pain of two FA Cup semi-final defeats for our club Stoke City in the early 1970s at the hands of the Gunners – I then learned about Manchester United’s early history in the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway company’s carriage works in Newton Heath on the eastern fringes of the city. I discovered that West Ham United’s roots were in a shipyard in London’s docklands. And most crucially for me, Dad recounted that Stoke City had similarities with Manchester United in that the club was formed – originally as Stoke Ramblers – by railway workers.

But another football club – one that was further down the food chain – strangely caught the imagination, and it was down to their name. That club was Frickley Athletic, an old colliery team based in South Elmsall but named after the Frickley Colliery that was opened on the estate of Frickley Hall. By the mid-1980s they were hosting Arthur Scargill rallies during the Miners’ Strike and at one point were the second highest placed team outside of the Football League.

The more I discovered about football, and the more Stoke City matches that I attended with Dad made me realise that there was a deep connection between the game and working class, industrial communities.

1984 wasn’t the best of years for my family. It saw the start of the yearlong Miners’ Strike which although didn’t affect my family and I directly, it impacted greatly on families in and around our village and across the wider North Staffordshire area. And furthermore, it contributed to the spiral of decline that the region is yet to recover from.

But the main reason that 1984 wasn’t particularly good for us was that we lost both of my grandads within the space of a few weeks early in the year. As a result, most of the year seemed quite miserable, and while you don’t necessarily grasp these kind of things when you’re young, hindsight can be most informative. Both of my parents had lost the most important male figure in their lives almost simultaneously, and both were grieving in their own way while needing each other at the same time; I get it now. The house was enveloped in dark clouds for months, and Stoke City certainly didn’t raise much cheer for both Dad and I; a dreadful end to the 1983/84 season – Graham Taylor’s Watford side visiting the Victoria Ground to give the Potters a 4-0 hiding sticks in the mind – merged into a disastrous 1984/85 campaign which saw Stoke relegated from Division One having broken all sorts of records along the way.

However, although the football was pretty grim around that time, 1985 was a much better year. It almost felt like my parents had sat down on New Year’s Eve and said, ‘…right, this new year is going to be a good one.’ The summer seemed endless and I only remember sunny days. And central to those sunny days for my friends and I was football. Hours and hours on the municipal pitches on the outskirts of our village, with the old Chatterley Whitfield Colliery providing a spectacular backdrop. Chatterley Whitfield was one of the country’s most famous pits, and was the first to produce one million tonnes of coal in a year. But by 1985, it was relic having closed eight years earlier and by then was a popular museum. Chatterley Whitfield has its own unique atmosphere, and it has haunted my imagination the whole of my life; today, while those municipal pitches endure and continue to be the fields of dreams for the area’s youngsters, Chatterley Whitfield stands silent, awaiting new life.

Towards the end of the year, I started to take my first steps into playing competitive football. The 59th Newchapel Boy Scouts were based in my village, and I was a member of the cubs group, and most pertinently to this story, part of the cubs football team, which was mainly made up of school friends. We had all known each other from a young age and were all close, and as 1985 became 1986, our cubs team was playing regular friendlies with other similar teams, and the team began to get tighter. Eventually, the dad of one of our group – a local legend, Mark Longshaw – who had played a bit himself, made the suggestion that the team became more formalised with a view to entering the Lads and Dads League in the nearby mining town of Biddulph. It was a logical step, and in May 1986, Newchapel United Football Club was formed. During that summer, we played friendlies with other lads and dads teams across North Staffordshire, and initially, we got turned over on a regular basis. One particular game has always stuck in the mind, a crushing 17-0 defeat at Knutton. However, it wasn’t the humiliating result that has remained with me. After the final whistle, the gentleman that managed the Knutton side – I have forgotten his surname in the mists of time, but I do remember him as Pat – wandered over to give my crestfallen Newchapel United team a little pep talk, which he concluded with, ‘…and remember this, football is a four-letter word – work.’ I was just about to turn 10 years old, but Pat’s words have always stuck with me.

As I reached adulthood, my own footballing dreams were receding into the past, and I simply played the game on and off on a recreational basis, while continuing to watch Stoke with Dad. Those post-relegation years had tended to be pretty much average with the occasional high point, but things changed with the arrival of two managers, both of whom greatly valued work, ‘got’ The Potteries and its people, and both built very good teams in the image of the city’s most famous industry.

The first of the two was former Celtic and Manchester United legend Lou Macari. Lou arrived at Stoke with the club at its lowest ebb. Following relegation to Division Three, the Potters finished the 1990/91 season in their lowest ever league position. However, Lou got to work and built a new team that he led to a Wembley triumph, and promotion back to the second tier after a title triumph during the 1992/93 season which included a club record unbeaten run. Lou eventually left for his beloved Celtic after a barnstorming start to the 1993/94 season, though returned 12 months later after the sacking of the dour Joe Jordan and his own dismissal at Parkhead. Lou once again built a very good side that went close to winning promotion to the Premier League – a play-off defeat to Leicester City halted the upward trajectory – before leaving the club for a second time on the eve of the club’s move from the Victoria Ground to the Britannia Stadium.

Like Lou Macari, Tony Pulis had two spells with Stoke separated by one season, and like Lou, Tony Pulis spent a season managing a team in green and white while away from The Potteries, Pulis’ team while in exile being Plymouth Argyle. But while Stoke just missed out on returning to the top flight under Lou Macari, Tony Pulis got them there, thus beginning the Pulisball era (‘…could they do it on a cold windy night in Stoke?’) whereby Stoke became an established Premier League club, reached a first ever FA Cup final, and played European football for the first time since the 1970s. Pulis left the club in 2013 after a wonderful seven season spell, and left solid foundations on which Mark Hughes built the Stokealona team of Bojan, Arnautovic and Shaqiri, before it all went horribly wrong.

Lou Macari and Tony Pulis were two different but similar managers. Both developed a deep understanding and fondness of the city and its people. Both placed a huge emphasis on hard work and team spirit which created a bond with the club’s support. And both of them loved a maverick free spirit who would add a bit of flair and creativity to the mix. Lou Macari created sides with a solid back line – think Ian Cranson, Vince Overson and Lee Sandford – and added someone like Mark Stein. Tony Pulis pulled together a group of ‘waifs and strays’ and added the likes of Ryan Shawcross, Robert Huth, and Rory Delap while a Ricardo Fuller sprinkled some stardust over it all. And that is basically the pottery industry: heavy industry, harsh conditions, hard work, while a good helping of innovation and creativity delivers an end product that is essentially a work of art. It is no coincidence that Lou Macari and Tony Pulis are Stoke City’s most popular and successful managers in modern times.

Aside from the 5-0 triumph over Bolton Wanderers in the 2011 FA Cup semi-final, the one game that perhaps summed up the Pulisball era was a backs-to-the-wall 10-men win over the newly minted Manchester City on a freezing cold January afternoon at the Britannia Stadium in early 2009. After Rory Delap received a harsh red card, the Stoke support generated the noisiest, harshest atmosphere that I have ever experienced in more than 40 years following the club; the supporters became that metaphorical eleventh man. Stoke nicked a goal shortly before half-time and then worked and worked and worked until the final whistle, securing a famous 1-0 win. And that was to be my last Stoke City game for a little while, as I was pulled in a slightly different direction.

At the time of Stoke’s first season back in the big time, I was living in Biddulph, a few miles north of the city, and so my true local club was Biddulph Victoria, a non-league side that competed in the Midland Football Alliance, and who played their football at the Tunstall Road Sports Ground which was developed on land donated by prominent Victorian industrialist Robert Heath. The facility is managed by a trust, and also includes a cricket ground, tennis courts, a bowling green, and a social club.

A week after Stoke’s win over Manchester City, I read in our local paper that the Vics were struggling financially, with the club’s chairman Terry Greer making an appeal for help.

I responded to that call, and initially helped to raise a bit of money. And at the club’s AGM at the end of the season, I became the club’s treasurer and development officer, and was greatly looking forward to getting stuck in. However, within a month or so of my appointment, the Vics were given two years notice to quit by the trustees that managed the sports ground, who stated that they no longer wanted a semi-professional club playing their football at Tunstall Road. At the end of the 2010/11 season – despite efforts to find another home – Biddulph Victoria folded, and an historic local football club had disappeared.

By that point, the management committee had agreed to move to nearby Alsager Town who had been facing their own challenges. Alsager Town compete in the North West Counties Football League, and are nicknamed the Bullets due to the former presence of a Royal Ordnance Factory at Radway Green on the edge of town, ironically a place where my dad worked for a spell in the mid-1980s. Indeed, the club’s home – Wood Park – is located alongside the Radway Estate, a housing estate built to house munitions workers at Radway Green.

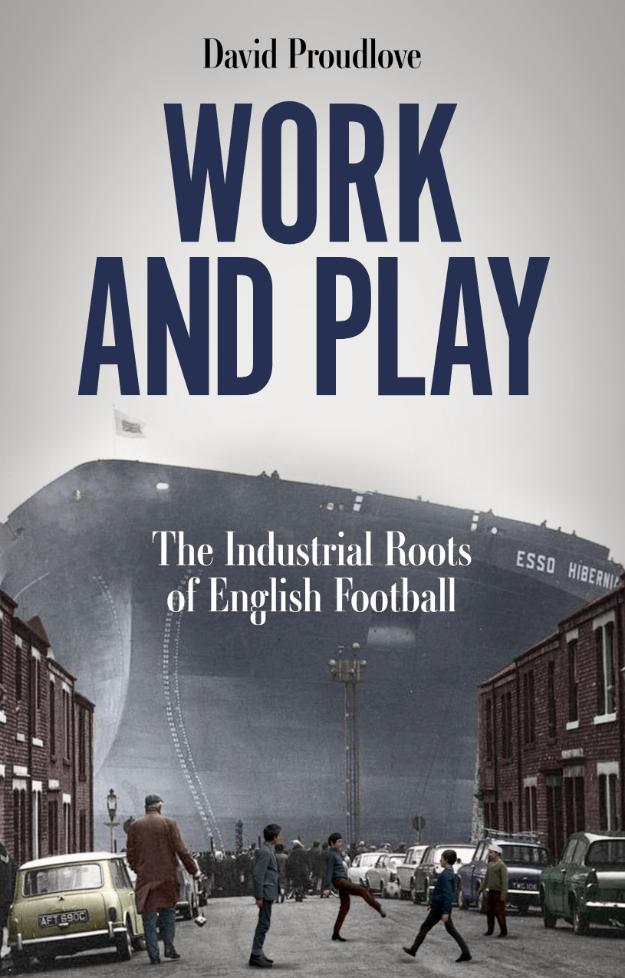

And it was during my time with Alsager Town when the lightbulb moment occurred for my latest book, Work and Play: The Industrial Roots of English Football. One chilly autumn evening shortly after the start of the 2020/21 season, the Bullets were hosting Vauxhall Motors at Wood Park. Before the game kicked-off, I was in the middle of doing some pre-match jobs when I got chatting to a gentleman from the Vauxhall Motors management committee, and the talk got to clubs that were founded as works team, Vauxhall Motors obviously being one. There were quite a few playing their football in the North West Counties Football League at the time – the likes of Avro and Cammell Laird 1907 for example – and obviously big clubs such as Manchester United and Arsenal.

On returning home, an hour or so on Google had got the creative juices flowing, and ultimately took me on a journey that took in visits to big cities, former coalfield communities, the shipyards on the banks of the Mersey, and railway towns where I examined the foundations of some of English football’s most famous clubs, and how the relationship between industrial communities and football continues to endure at a local level throughout the grassroots and semi-professional game.

Although I had always appreciated the connection between football and industry, the crafting of Work and Play has led me to understand that that connection is much deeper and wider, and is actually hugely significant. In most cases, the identity of industrial communities is central to their football clubs and vice versa, and in these fractious times, is growing in importance. Many local clubs are becoming more like community hubs, and are keeping alive the spirit of self-help in areas that have been effectively abandoned from a policy perspective for many years. Indeed, in some place, these football clubs are the last remaining link with the industries that once sustained them.

Just as times are tough for industrial communities, times are just as tough for their football clubs, but there is potentially hope. As many become disillusioned with the upper echelons of the game, some are finding hope and solace with their local clubs, and it is here where their future lies. People are making informed choices in order to seek out a different experience; and because of what they get, they will give back. It’s not dark yet.

We all know the modern story of English football, but there is another side to it. And you can read it in Work and Play.

Note:

When Football Leaves Home, and Work and Play: The Industrial Roots of English Football is available via the publisher’s website:

Pitch Publishing - https://www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

Biography

David Proudlove is the author of When the Circus Leaves Town: What Happens When Football Leaves Home and Work and Play: The Industrial Roots of English Football. He wrote a weekly column for the North Staffordshire daily newspaper The Sentinel for 10 years, and was also a regular contributor to the former Stoke City fanzine Duck. His work also appears in various other publications including Turnstiles and the Birmingham Dispatch, while he is a regular contributor to the Football Heritage blog. David also regularly collaborates with artists and other writers.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/submitted-news-images/Smelting-knife.png)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/250630-SciFest-1-group-photo-resized-800x450.png)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/submitted-news-images/Way-youth-zone-August.JPG)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/Arthi-Arunasalam-teaser.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/submitted-news-images/Muslim-woman-playing-football.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/submitted-news-images/Business-School-800x450.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/submitted-news-images/University-of-the-Year.jpg)